Writing to See in the Dark

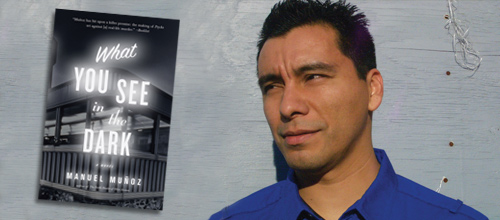

Author Manuel Muñoz finds inspiration in ‘Psycho’

by Neil Ellis Orts

EXPANDED VERSION FOR THE WEB

When I was a grad student at Columbia College Chicago, I had a part-time job as an editorial intern at Northwestern University Press. One day, I was handed a manuscript that was nearing press and was asked to read it for any glaring problems.

That book was Zigzagger, a collection of short stories by Manuel Muñoz. I think I might have found a couple of things to circle and show the managing editor, but I also found a new favorite author. His stories of life in southern California not only captured my imagination, they also enlightened some of my own personal puzzles about life.

Muñoz has since published a second short-story collection, The Faith Healer of Olive Avenue, and his first novel, What You See in the Dark, has just been published by Algonquin Books. In this new book, Muñoz explores life and death in Bakersfield while Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho is prepared and filmed in the surrounding community.

Via e-mail interview, I talked to Muñoz about his writing process, his audience, and his experiences as a gay Latino writer.

Neil Ellis Orts: Had you attempted a novel before What You See in the Dark? Is going from short stories to novel length a challenge? If so, how?

Manuel Muñoz: I have two failed novels in a box somewhere. I did not write stories as an MFA student [Muñoz received a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing from Cornell University], which, in some ways, was quite liberating. If I earned any scars in workshop, it was from submitting choppy, rambling chapters of a novel with parameters I didn’t quite understand. Stories helped me focus once again on control, but I went through five drafts of this novel before I settled on the final structure—and it wasn’t until the fourth draft that I understood some of the moves I had made and how I could potentially reach a unity between the narrative and the chosen style.

Obviously, Psycho is a movie you know something about. How much of the “making of” chapters in What You See in the Dark is the result of research?

I read several of the books about the making of the film, but also delved into most of Hitchcock’s oeuvre from about Notorious onward, as well as many scholarly essays and more pop-culture approaches, to familiarize myself once again with his distinctive methods of storytelling. The film was largely shot on a studio set, but a crew did go out to shoot material for rear-projection shots of the old Highway 99 and in the foothills surrounding L.A. Janet Leigh’s participation in this was minimal (as was Hitchcock’s in some cases, as sometimes such footage is handled by a secondary unit). That’s one of the reasons I introduced her in the process of arrival—the chapter asks us to focus on her via an action, rather than by who she might be as a persona.

Did you ever consider naming Hitchcock and Leigh by their real names? If so, how did you decide to go with “the Director” and “the Actress”? What effect are you after by using the generic (if capitalized) title rather than the name?

I was inspired to use a capitalized title after I read Joyce Carol Oates’s Blonde, her fictionalized account of the life of Marilyn Monroe. In that case, the title serves as a marker of identity for a woman who was born as Norma Jean, but becomes “known” as Marilyn. I enjoyed how the novel asked me to use my knowledge of the Monroe mystique in helping to shape the character. In my novel, using the capped title is also a way to admit how daunting it is to take on such characters—as film lovers, we think we already know who they might be, so the titles are there to insist that we really don’t. We know them, essentially, only as their roles.

There are no overtly gay characters in this novel, yet I’ve heard some people speak of it as having a “gay sensibility.” What are your thoughts on that phrase, or, to put it another way, your novel’s “gay aesthetic”?

I’m certainly sympathetic to the question and have my suspicions about why our community continues to circle around the idea. But our collective experiences (though not necessarily our shared ones) cover such a vast array of class, culture, age, and gender roles that it’s impossible to put a finger on how all of these factors filter into a definitive “sensibility.” As for this novel, my guess is that it has a focus on how and why women perform—Teresa as a singer and the Actress in her own medium. That might be enough for some readers to qualify this book as a queer text, but I’m not so sure that I would argue this myself.

As an out gay man, you seem to move among the mainstream, albeit literary, crowd (as opposed to the distinctly gay literary circles, gay presses, etc.). How has this been for you? Do you find you have to navigate that world in a particular way?

It’s intriguing to me to see you use the word “mainstream”—I think I’m far from that. The question also suggests that not being part of a gay literary circle means that access to a “literary” crowd might be a given. I see myself in an entirely different space, actually: I see myself, first and foremost, as a Chicano writer. The Chicano/a writing community was very, very quick to support my work when my first book appeared in 2003. Chicano/a academics also reacted swiftly: they began writing critically about my work almost from the get-go (an act which helps cement a writer’s work in many frames, historical and otherwise).

I received very little of that enthusiasm from the queer community, whether from bookstores, review outlets, or academics. So I chose to hear the silence for what it was. I did my best to move in the community that was receiving me openly and without equivocation. Queer lit, at best, was a mixed bag—I’ve been very honest about that for some time now.

Your first book, Zigzagger, was published at Northwestern University Press under their Latino Voices imprint. Do you find you have to navigate the literary world in a particular way as a Latino writer?

This may have been why the queer press largely ignored the book, even while it enabled me to get the attention of the broader Latino/a community (not just the Chicano/a readers) in general. Being published this way forced my hand, as the imprint showcased questions of ethnic identity and politics, and positioned the stories as being in dialogue with those concerns. Queer lit simply wasn’t ready for that. In fact, if it hadn’t been for a Latino colleague at Lambda Literary doing a roundup of recent Latino work, I doubt that even my second book would have been reviewed by that organization. That still sticks in my craw.

When I’ve spoken of your work to other people, I usually reference “Zapatos,” the short-short [very brief story] in Zigzagger. After I read that story, I felt like I learned something about myself—that you had explained some things about my life. Do you hear this sort of thing from your other readers, that your stories bring epiphanies that explain their lives?

Absolutely—I hear this all the time, and it pleases me to no end. The function of literature, as I see it, is to serve as an opportunity for kindred spirits to somehow meet. We share more common ground than we think, and stories help us understand that. In a good story, the burden is on both a writer and a reader equally—we both must come to the table with a willingness to be vulnerable to the story. It’s all in the service of empathy. Look at the recent “It Gets Better” campaign: by relating a story, another’s pain may be soothed. This is at the heart of why we tell stories, right? Brilliant! But this also shows us why all possible stories need to be let in, need to be expressed. The campaign has been criticized—and rightly so—for catering mostly to men. It does get better, but judging by the videos, it only gets really good if you’re white, male, urban, and middle class.

I’ve always been impressed with your ability to make people we’d normally find unlikeable into sympathetic characters. (For example, the father of the kid who jumps from the hotel balcony in The Faith Healer of Olive Avenue.) Do you set out to create sympathy for people who act reprehensibly?

This is very intentional, for exactly the reasons I stated above. We have more in common with one another than we think. Sympathy doesn’t necessarily have to mean we agree with a reprehensible act. But it might mean that we are willing to be conciliatory. We are willing to forgive. We are willing to look past what we think we know is right and good in the world. Given the harsh, angry tone in our country, I think that’s one of the most valuable things offered by fiction—it’s our chance to see how grace can truly be applied to life. Good fiction can show us how we might be willing to listen, maybe even understand.

What You See in the Dark is available from Algonquin Books (workman.com/algonquin).

Neil Ellis Orts is a frequent contributor to OutSmart magazine.