An Amazing 30-Year Evolution

A new era begins for Legacy Community Health Services

(See also additional information on the clinic’s timeline and locations. Plus Meet Katy Caldwell, Legacy Community Health Services’ executive director.)

Legacy Community Health Services traces its roots back to Montrose Clinic, established in 1981 as a public service by the gay community for the gay community. Originally organized to provide testing for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), Montrose Clinic was inadvertently poised to become Houston’s first and continuing response team to the AIDS epidemic.

Over the past three decades, the clinic, like Topsy, “just growed.” It has moved to larger quarters five times to meet the growing demand for services, and it has merged with two other organizations—the Assistance Fund and Body Positive Wellness Center—to create the new organization now known as Legacy Community Health Services. As it grew, its focus on service (rather than profits) opened the doors to innovation, with its in-house development of the Houston Clinical Research Network and the Monte Frost Eye Care Clinic. Although it was founded as a gay service organization, the clinic has become a model healthcare facility for the entire city, even as it continues its specialized services for people living with HIV and AIDS.

Gay Activist Ray Hill: A Lone Voice in the Wilderness

The first record of a health initiative specifically for gay men in Houston comes from our pioneer gay activist Ray Hill, who remembers creating a tri-fold flyer about STDs in the 1960s. “I left them in the gay bars,” he says. “It addressed the symptoms and treatment of syphilis, gonorrhea, and venereal warts.”

Recognizing the high rate of STD infection in Houston’s gay community, Hill went to a public health clinic once a month to get tested and encouraged other gay men to follow his example. But the rapid spread of STDs outpaced his efforts. There were reports of rude treatment by staff members at the public clinics. Many gay men found it embarrassing to admit to anal intercourse, and revealing sexual partners effectively outed both the patient and his partners.

Fortunately, by 1976, someone else had also begun to recognize the problem. “Dan the VD Man,” a public health services employee, was responsible for tracking down the sexual partners of infected men who sought treatment. He knew that gay men were not getting tested in sufficient numbers, and decided to try taking the STD tests to them.

Dan contacted the owner of Dirty Sally’s, a popular gay bar, and the owner put Dan in touch with Hill. Together, the two developed a weekly “STD Testing Night” at the bar. The idea worked well enough that Dan enlisted the Health Department’s mobile testing unit and parked it outside other gay bars. The favorable response led to the development of an ongoing Houston Health Department program for testing gay men.

In 1978, Dan handed his STD-testing work on to “Mother Ruth” Ravas. Mother Ruth became so familiar and popular that she was chosen as a 1980 Pride Parade Grand Marshal.

Organizing an LGBT Community

“Before the giant anti-Anita Bryant rally in 1977, I thought of the gay community as nothing more than a group of bars,” says Hill. “But then 6,000 local GLBTs showed up to rally against Bryant at the Hyatt Regency Hotel on June 16, 1977. The police chief had planned on 50 demonstrators. That’s when I realized that a gay community did exist, and it could be mobilized. Anita never knew how much she did for the formation of Houston’s organized gay community!”

After the Hyatt demonstration, Hill felt it was time to bring the community together again and lay the groundwork for LGBT institutions. He worked with other local activists to organize Town Meeting I, held in the Astro Arena on June 25, 1978. Through Hill’s encouragement, various groups of people formed committees to draft resolutions for the meeting. Among those resolutions was one that addressed community health.

The resolution didn’t call specifically for a community clinic, but it did provide the spark that led interested people to begin brainstorming about a community health effort. Richard and Robert O’Brien, gay brothers who were practicing physicians, began holding meetings with other Houston physicians including Gary Brewton, Diedier Piot, and Kendall Hamilton. Marion Coleman remembers attending their meetings in Montrose restaurants. “I was the token female,” she laughs, “but all the talk about male STDs was quite alien to me.”

Toward the end of 1980, in a mass mail-out, Richard O’Brien and Mother Ruth appealed to the community to help fund a “Montrose Clinic.” “The clinic may well be the most important way we have of demonstrating to the world our serious intent to take care of our own needs,” the letter stated.

Mother Ruth and activist Danny Villa organized “The Zap Clap Revue,” which was staged in May of 1981 at Babylon Disco. Planning and fundraising continued, and Montrose Clinic opened its doors in rented quarters at 104 Westheimer on October 6, 1981. STD tests were given three nights a week and on Sunday afternoons. No fees were charged, but donations were encouraged. The facility quickly gained the nickname of “The Clap Shack.”

Medical supplies for the clinic were provided by the Houston Health Department, which also performed the lab work. Volunteers handled testing and administrative functions. Physicians took turns donating their time one night a week to treat clients with STDs. Over the years, volunteer physicians have included Patsy Salvado, Shannon Schrader, Gordon Crofoot, and Gary Brewton.

The Dawn of an Epidemic

Between the Zap Clap Revue and the actual opening of Montrose Clinic, something occurred that would profoundly impact the future of the organization. On June 5, 1981, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) published a report describing cases of a rare lung infection, Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), in five young, previously healthy gay men in Los Angeles. All the men had other unusual infections as well, indicating that their immune systems were not working. Two had died by the time the report was published.

The national media picked up the story, and the CDC quickly became inundated with reports of PCP and other opportunistic infections among gay men. Cluster cases of a rare and unusually aggressive cancer, Kaposi’s Sarcoma (KS), were reported among a group of gay men in New York and California. The media labeled it “the gay cancer.”

But the reports didn’t take everyone by surprise. Houston physician Didier Piot, a transplant from Toronto, had first observed something medically sinister in a patient in Haiti in 1977. Then, in Toronto in 1978 and 1979, he treated Gaëtan Dugas, a flight attendant for Air Canada—the man who later became known as “AIDS Patient Zero.”

A Mysterious and Relentless Killer Emerges

In September 1982, the CDC began calling this group of illnesses that was increasingly appearing in the gay community “AIDS,” an acronym for “Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome.” Information about the mysterious disease was slowly coming together, and in May 1983 the Pasteur Institute in France announced the discovery of an “LAV” virus that was associated with AIDS.

The Houston Gay Political Caucus (GPC) and Citizens for Human Equality (CHE) worked with the Montrose Clinic to get the word out and to raise money for further educational efforts. The O’Brien brothers often used their North Boulevard mansion for fundraising events.

Then in 1984, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and France’s Pasteur Insti- tute announced that the cause of AIDS had been identified, but no cure was in sight. A diagnosis of HIV infection was essentially a death sentence, with the only question for infected patients being how long it would take for HIV to progress to full-blown AIDS. And at the time, HIV was impossible to detect until the symptoms of a broken immune system began to emerge.

Houston’s First Line of Defense

In 1984, Montrose Clinic began its Program for AIDS Counseling & Evaluation (PACE). This program offered a review of a client’s health history and recent complaints, a complete physical examination, evaluation of blood and skin tests, and referral to a specialist if necessary. This was the community’s de facto first line of defense against AIDS, and it was clear that the clinic needed to double its space. Thomas Audette, the clinic’s executive director, went looking for larger quarters. Dr. Richard Grimes, a member of the clinic board, helped in the search. “It was nearly impossible to find rental space,” he says. “Most Realtors felt they wouldn’t be able to rent the space again because of the stigma of it being an AIDS clinic.” But Audette and Grimes persisted, and the clinic soon moved to a larger space at 803 Hawthorne.

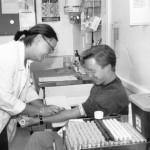

The move was well-timed. In 1985, a blood test for HIV became available. The Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) detected if a client’s body was producing antibodies to combat HIV. ELISA was used by blood bank centers to ensure the safety of donated blood. Gay men descended on the centers, asking for the test.

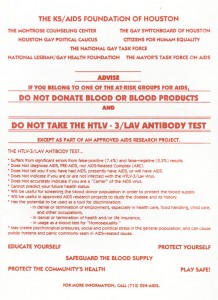

When the ELISA test first became available, a coalition of national, state, and local LGBT organizations issued a warning to the community that they should not attempt to donate blood and should not take part in any testing that would leave a paper trail.

When the ELISA test first became available, a coalition of national, state, and local LGBT organizations issued a warning to the community that they should not attempt to donate blood and should not take part in any testing that would leave a paper trail.

Nelson Vergel was among the first Houstonians to be tested. Rev. Ralph Lasher, a volunteer counselor, gave Vergel the news that he was HIV-positive. Asked how you tell someone they have AIDS, Rev. Lasher replied, “You take a deep breath before you go in.”

Vergel became a volunteer counselor soon after receiving his test results. “I used to leaf through the test results for the current session and pick out the positive ones,” he says. “I wanted a client to immediately feel a connection with someone else in their situation. That waiting room was the scariest place in Houston. Fear was written all over everyone’s faces as they waited to be called and told their HIV test results.”

On October 2, 1985, actor Rock Hudson died of AIDS. “The Clinic was overwhelmed with clients coming in for testing as a result of that news,” Grimes remembers. “We were processing 600 to 700 tests a month.”

Amidst the Gloom, the First Rays of Hope

During those years when little hope endured, many patients died painful and lonely deaths with no friends or family to comfort them. When a death was about to occur, it was “time to call Ray.” “I’d walk into their room, with just a T-shirt, jeans, and sneakers on—no gowns, no masks, no gloves,” says Hill. “I’d sit on the bed and hold them in my arms.” Once they felt comfortable and not alone, Hill would whisper softly to them, “It’s okay to let go.” He stayed and held them until they transitioned.

“In the first few years of AIDS, there was little we could do for patients,” says Dr. Wayne Bockmon. “Sometimes all we could do was cry with them.” As a gay man, he felt quickly drawn into the community’s health crisis.

“AZT was the first ray of hope,” says Piot. “It was able to interrupt the reproduction cycle of the HIV virus.” Piot remembers that patients would have to take AZT every four hours, and they were given a pillbox with a timer set into it. “It used to be a common experience at the River Oaks Theater to hear timers going off during a movie.”

The drug could be hard to find. Dr. Grimes’s wife did a study of gay men and found that most of those living with HIV had a stash of AZT hidden away. It was not uncommon for Montrose residents to break the law and give away remaining unused AZT when a partner or close friend died. People met in parking lots to exchange the pills after being alerted through an anonymous network.

Initial optimism faded as the virus proved its ability to quickly mutate—and once it did, AZT no longer had much impact on it.

Montrose Clinic once again found the demand for help too great and its quarters too small, so by 1988 it had again doubled its space by moving to 1200 Richmond Avenue. That year, Audette died and Lasher took over the reins.

Incremental Advances and a Breakthrough

In 1989, Montrose Clinic formed the Houston Clinical Research Network to allow more clinic patients to access investigational drugs. The network became one of 12 test sites sponsored by amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research.

“We were able to do two important things,” says Chris Jimmerson, an early clinic employee. “First, we added to the collective knowledge about AIDS treatment, and second, we opened the way for our clients to try additional options if AZT no longer was effective.” He estimates that over 2,000 clients took part in the tests.

1989 also saw the introduction of aerosolized pentamidine as a prophylactic against PCP. The Diana Foundation funded the establishment of pentamidine treatment stations. When Jim McIngvale (“Mattress Mack”) saw them in a local news report, he donated recliners to replace the plain chairs.

The clinic continued to test and treat, the client load continued to grow, and the death toll continued to rise. Once again in need of expansion, a $2 million capital campaign was started in 1992.

Dr. Grimes spearheaded the fundraising effort, assuming the role of the straight front-man for meetings with potential donors. “I used to flash my wedding ring and talk a lot about my grandchildren,” he remembers.

The clinic purchased what was formerly the Hollywood Motel at 215 Westheimer. “One thing that really grabbed our attention was the fact that there were separate rooms, all with running water,” says Grimes. “We saw that as a good framework for a structure with treatment rooms.”

The old by-the-hour motel was completely rebuilt, and the clinic moved into its new facility in 1994. A formal dedication was held in early 1995, and later that year the Monte Frost Eye Clinic was added to deal with CMV retinitis, a common AIDS condition caused by the cytomegalovirus.

In 1995, the death toll spiked. Since 1991, Montrose booksellers had been unable to keep up with the demand for Derek Humphrey’s Final Exit: The Practicalities of Self-Deliverance and Assisted Suicide for the Dying. But remarkably, the toll finally began to lessen in 1996—as did demand for the book. Antiretroviral combination drugs were proving to be successful in stopping the progression of HIV. It was a new era for Montrose Clinic and AIDS treatment.

In 1996, the year that former Harris County Treasurer Katy Caldwell became Montrose Clinic’s executive director, the clinic introduced women’s health services, including pelvic exams, PAP smears, breast exams, and referrals for mammograms.

As the new millennium arrived, HIV had become a basically manageable condition—but one that required a team of HIV specialists and proper administration of drug therapies. The clinic saw this as its primary mission as it continued to be the health services provider of choice for the gay community.

Addressing the Psychological Impact of AIDS

Back in the 1980s, AIDS physicians realized that their clients were often in great need of psychological support. Dr. Shannon Schrader remembers, “Some people purposely booked appointments more often than they needed. I finally realized that they were coming just for an encouraging pat on the back and a few minutes talking with a friendly party.”

Houston psychotherapists and business partners Miles Glaspy and Bill Scott were also seeing the same need. In 1988, they launched Body Positive as a solution (later known as the Body Positive Wellness Center). The group developed a program to educate and support people living with HIV. A buddy system matched up volunteers who were HIV-positive with persons who had just been diagnosed.

Their efforts included peer support groups, HIV-positive socials, stress reduction classes, financial planning, caregiver training, and Christmas caroling in local AIDS wards. The Body Positive’s fruit and vegetable garden provided 500 pounds of food each year for Stone Soup Food Pantry.

The rise of the antiretroviral drug combinations ultimately affected Body Positive’s existence. Involvement began to decrease, and funds were harder to come by. But in 1997, Vergel joined Body Positive’s board and by 1998 had convinced them to open a wellness center in the 3400 Montrose building. In 2000, they merged with Montrose Clinic and moved to 3311 Richmond, where they added a complete workout room with personal trainers. “I made sure all the trainers were also HIV-positive,” says Vergel. “People with AIDS often didn’t feel welcome at local gyms, or else they felt insufficient with their limited capabilities.”

The center also includes a nutritionist who helps people develop a healthy eating regimen. Vergel calls the efforts “salvage therapies.” “People with HIV are living longer, but they need a way to rebuild their health,” he says. The clinic hopes to start a new phase of therapy by working on wasting and fat-gathering syndromes.

Funding the Fight

Houston’s socialites had largely ignored AIDS until 1986, when Houston’s “first lady of philanthropy,” Carolyn Farb, organized “An Evening of Hope” to benefit the Bering Foundation. “Nearly 40 percent of the people I could usually count on didn’t even return my calls or messages,” Farb remembers.

But Farb pressed on and raised $100,000. More importantly, she finally managed to break through the wall of resistance against AIDS fundraising events.

In 1987, designers Michael Dale, Betsie Weatherford, and Lynn Billings Etheridge started a local chapter of the national Design Industries Foundation Fighting AIDS (DIFFA). “We had high-profile clients we had worked with for years,” says Dale. “They wanted to help, but they needed a comfortable vehicle. DIFFA offered them that.”

Dale knew that local designers knew how to give great parties and whom to invite. Over the next few years, DIFFA organized numerous glitzy fundraisers, and by 1996 had raised over $2.7 million.

In 1987, the Institute for Immunological Disorders opened a for-profit AIDS hospital. It was staffed by some of the best AIDS physicians in town. But so many patients were indigent that the hospital was unable to meet financial demands, and it closed down.

Insurance premiums for AIDS patients were a big problem. COBRA legislation mandated that employees could keep their health insurance for 18 months after leaving a job on disability—but premium payments were at full cost. Additionally, Social Security took two years to kick in with disability coverage, so AIDS patients had a six-month gap with no coverage, or extremely high insurance premiums.

The Institute for Immunological Disorders contributed $25,000 to DIFFA-Houston—funds that had been set aside to help people pay their insurance premiums when they could no longer work—and asked DIFFA to take on this function. Between the $25,000 and the DIFFA efforts, the Assistance Fund was born. DIFFA continued to administer the Fund until 1989, when the board felt the Fund needed to be an independent service provider.

Designers Susan Strong and Jim McNabb took up the challenge. From their office in Rice Village, the Assistance Fund continued to help with insurance and medication costs for those who had no money. In 1994, they were able to purchase a building at 1515 Jackson Boulevard. Volunteer contractors helped remodel the space, and on June 25, 1995, the Assistance Fund opened its new headquarters with Ken Malone at the helm.

But as the new antiretroviral combination treatments began to dramatically slow the AIDS virus, the Assistance Fund’s clients were living longer. It was also becoming more and more difficult to attract money for AIDS causes, so in 2005 the Assistance Fund merged with the Montrose Clinic, and the combined organization took on the name Legacy Community Health Services.

Beyond AIDS

Since 2005, the clinic has had the opportunity to broaden its healthcare delivery programs throughout Houston. AIDS was no longer the dark specter that had hung over the gay community for so long, and the clinic began to develop other programs to complement its HIV-related services.

In the fall of 2005, the clinic helped over 600 Hurricane Katrina evacuees with medical care and replacement of HIV medications that were lost during the New Orleans disaster. About one-third of the evacuees assisted by the clinic were HIV-positive.

In 2006, Legacy partnered with Walgreens to open a pharmacy in their 215 Westheimer location. Legacy owns the medications, but contracts with Walgreens to dispense them.

That same year, a satellite clinic opened at 5602 Lyons Avenue in Houston’s Fifth Ward, a traditionally black neighborhood where many residents are indigent.

Through the efforts of executive director Caldwell, in 2007 Legacy was granted full status as a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) offering primary care services to Houston’s uninsured and underinsured. This opened up a whole new source of funding and widened the scope of their responsibilities.

In 2009, Legacy announced a $15 million capital campaign for a new building to consolidate three of its locations into one state-of-the-art facility in Montrose. Groundbreaking occurred in 2010, the same year that Legacy began operating their Southwest Community Health Center at 6441 High Star Drive. That facility had been run for 18 years by the Christus Medical Group, and primarily serves children and pregnant women.

Later in 2010, Legacy opened the Baker-Ripley Clinic at 6500 Rookin Street inside the colorful Baker-Ripley Neighborhood Center. Services include family-practice primary care, family planning, behavioral health, and Legacy’s first dental clinic.

Legacy remains a healthcare provider with a strong core of HIV treatment services—but because they now offer a wider range of services, the clinic has access to more funds to provide even more extensive treatment for HIV patients. Since many of Legacy’s clients use the bus system, having a central building incorporating many services will make their lives much easier.

The new building at 1415 California Street was completed in the summer of 2011, and during the second weekend in September, the 215 Westheimer Road, 3311 Richmond Avenue, and 1515 Jackson Boulevard locations were merged into the new 40,000-square-foot facility one block north of Westheimer. The first two floors house 34 exam rooms, and the third floor is being used to convert medical records into electronic form. The fourth floor is available for future growth.

The new building was designed to be “green,” with three giant oaks that have been carefully preserved. Environmental awareness is also evident in the rainwater collection system that irrigates the landscaping, special window tinting that dramatically lowers air-conditioning costs, and reserved parking for low-emission vehicles. There are even showers for employees who want to bike to work.

Katy Caldwell, Legacy’s executive director, speaks with pride and affection about the new building: “The trees that we have preserved on this site are living symbols to me. Their roots represent the deep roots Legacy has in the Montrose community, the large trunks speak to the strength that the clinic had during the darkest days of the AIDS crisis, the ever-expanding canopy symbolizes the refuge we give to so many in difficult times, and the green leaves and new growth represent the hope we have for the future.”

Looking back and looking ahead

Reflecting back on the worst of the AIDS years, most people who lived through it still wonder how we made it through such a terrible point in our community’s history. It was a challenge unlike any other the LGBT community had ever faced, and people came together in a way never seen before or since. A whole generation of young gay men found their lives interrupted for 15 years as they endured losses that most people only deal with in old age.

Unfortunately, new HIV infections are again on the rise in the gay community as HIV experts caution young people not to take HIV lightly. The virus still mutates around drugs, and some people have only one drug left with which to slow the virus. HIV medications are known to cause cardiac problems, and patients must limit their alcohol intake. Practicing safe sex is still essential.

During the past three decades, the organization now known as Legacy Community Health Services has gained great respect for the quality of its services and the compassion of its staff. Houston’s LGBT community and its supporters can be proud of the model for community healthcare they have created.

Legacy invites the community to join them at the dedication ceremony for their new building at 1415 California on October 16, 2011, to help them celebrate this newest advance in healthcare delivery for HIV clients. Even more importantly, Legacy wants the ceremony to help the community reflect on the past three decades, remembering with fondness and appreciation all the people who worked so hard for so long—and are a part of the legacy of Legacy Community Health Services.

Brandon Wolf is a frequent contributor to OutSmart magazine.

The author wishes to thank Christine Doby for her collaboration; Eric Roland, Sr. Director of Marketing & Communications, Legacy Health Care Services; Larry Criscione, Mike Kelley & Leif Hatlen at the Charles Botts Archive; and all the people who took time to reflect back on their memories of the last four decades.