Are All Fashion Designers Gay?

Edited by Valerie Steele. 2013 • Yale University Press (yale.edu/yup)

248 pages • 100 color Illustrations. Cloth: $50

‘A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk’

by Kit van Cleave

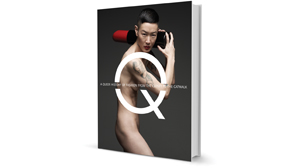

A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk is truly groundbreaking. From its eye-catching cover, featuring a nude and tattooed Jenny Shimizu (once Angelina Jolie’s lover), to full-color illustrations and photographs of clothing through the centuries, this new coffee-table book is both beautiful and informative.

It features seven essays by fashion experts and historians, discussing the long history of clothing as code for oppressed desire. While the era generally highlights the last two centuries, analyzing the work of Cristobal Balenciaga, Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, and Alexander McQueen, the essayists bring current fashion right up to activist wear from the last two decades.

And two of the essays, by Elizabeth Wilson and Vicki Karaminas, are about lesbian fashion. That’s news in itself, given that much 20th-century fashion was produced by gay men (with straight models), while lesbians were generally ignored, seen as having no fashion interest or taste at all.

Valerie Steele credits Fred Goss’s 1997 piece in The Advocate, in which he says, “The vast number of gay men and lesbians working in the industry [were] compelling proof that fashion owes its very life to the gay sensibility,” yet the fashion world remained “strangely closeted.” Today, many gay artists still aren’t open about their lives.

“Even people who are technically ‘out’ may not want to be labeled as gay or lesbian, because they don’t want their work to be stereotyped—or their own accomplishment minimized.” Besides, “It’s nobody’s business because it is irrelevant to my work,” they often say. Yet, Steele asks, can an issue as central to one’s sexual identity ever be irrelevant to someone’s creative work?

A major theme of this book discusses how “gay men and lesbians have evolved not only coded clothing practices by which they might recognize others with a similar sexual orientation or interest, but also a nuanced vocabulary for reading dress.” Steele goes back to the 18th century to discuss the molly, the macaroni, and the man-milliner.

“Throughout most of recorded history,” she writes, “people did not think of themselves as being gay or straight or bisexual; they simply engaged in certain sexual acts.” So as long as people didn’t perceive themselves as “having a particular sexual identity, they wore the same clothing as everyone else,” except for males who consistently assumed the passive role, “who might, in certain cultures, dress as women.”

Steele notes the emergence, around 1700, of a minority of adults in northern Europe “whose sexual desires were directed exclusively toward adult and adolescent males,” identified by a calculated “effeminate behavior in speech, movement, and dress.” Coverage of this group in the British press paid most attention to “effeminate sodomites” who gathered in inns and public houses to socialize and cross-dress”—the mollies.

Second in importance were the effetely stylish “macaronis” whose foppishness called into question contemporary ideas of masculinity. A third influence was the rise of the “man-milliners” who began to compete with female milliners who dominated the industry (tailors were male).

Of course, much European aristocratic court dress was extravagant, such as a “colorful silk suit embroidered with flowers, trimmed with lace and accessorized with diamonds.” Think John Malkovich being dressed by his servants as Viscount Valmont in the film Dangerous Liaisons (1988).

Peter McNeil’s “Conspicuous Waist: Queer Dress in the ‘Long 18th Century,’” Christopher Breward’s “Couture as Queer Auto/Biography,” and Shaun Cole’s “Queerly Visible: Gay Men, Dress, and Style 1860–2012” continue Steele’s detailed overview of fashion history. Featured are “bear” style, color coding with handkerchiefs, key placement, “clone” emphasis on masculinity, wedding dresses and suits, AIDS, political actions, and the “lipstick lesbian” era. So much material is incorporated here that readers will surely find new insights about their favorite designers and time periods.

For me, the two most interesting chapters were Elizabeth Wilson’s “What Does a Lesbian Look Like?” and Vicki Karaminas’s “Born This Way: Lesbian Style since the 1980s.” Wilson discusses the dress of the most famous lesbians of the early 20th century—Radclyffe Hall and Lady Una Troubridge—with a full-page photo of the two at home in their presenting clothes. Photos also accompany her discussion of Colette, Marlene Dietrich, and Greta Garbo (with Mercedes D’Acosta). To these women, “lesbianism could, after all, announce itself as a celebration of femininity and womanliness as much as an assertion of the independence conventionally associated with the masculine.”

Karaminas’s essay starts with Lady Gaga and moves to Britney/Madonna, k.d. lang, drag kings, and androgyny, “to give women a place at the crossroads of femininity and authority.” She points out that Ralph Lauren, Gucci, Emmanuelle Ungaro, Calvin Klein, and Prada have marketed designs to appeal to a lesbian sartorial taste.

This is a splendid book on the only art everyone is involved with—fashion and clothing. It’s superbly written and researched, and provides amazing illustrations.

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.