A Passion for LGBT History

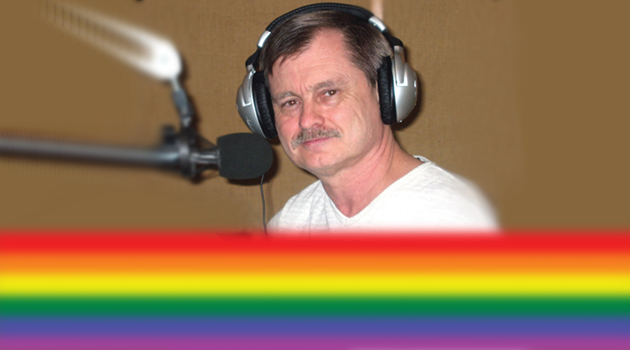

JD Doyle, 2014 Male Pride Marshal, has given us back ourselves.

by Brandon Wolf

When JD Doyle was in the first grade, attending a small country school in Ohio, he asked his teacher, “Which eye do you use to wink at a girl, and which eye do you use to wink at a boy?” His teacher didn’t know, so they asked the principal. The principal said, “Whatever is natural.”

It was an early expression of Doyle’s gay identity, and in this case, things went smoothly. But he would soon learn that whatever was natural to a gay man wasn’t acceptable to mainstream society. It took him another quarter of a century of soul-searching to sort it all out.

The rest is history—quite literally. Today, Doyle is widely known in Houston and beyond as an important LGBT historian. He is regularly sought as a subject-matter expert on queer music. His list of accomplishments is diverse, lengthy, and ever-expanding. This year he is—quite appropriately—a person making history. The community has chosen him as their 2014 Houston Male Pride Marshal.

Growing Up in the Midwest

Doyle was born and raised in Salem, Ohio, where his father worked in manufacturing and his mother was a homemaker. They met in Belgium during World War II. Doyle is the older of two boys.

Doyle’s early years were spent in a rural area outside of Salem, with no playmates his age. “I had to learn to amuse myself,” he says. The family eventually moved into the city when he was nine.

Thanks to the post-war baby boom, Salem was a small town with a big school. Doyle’s graduating class had over 300 students. Although he was not involved in sports or music, he did organize a French club. “It was me and 20 girls,” he says with a smile.

Doyle was an average student, until he discovered chemistry. He was fascinated with the subject because of a teacher who made it interesting. He studied hard, and began taking all of his classes seriously. When he sat for the National Merit Scholarships test, he scored 98 out of 100.

A Passion for Music

Doyle purchased his first record in 1961—The Peppermint Twist by Joey Dee & The Starliters. A regular at the local record shop, he asked the manager to save the outdated Top of the Charts lists for him.

Doyle was soon buying “girl group” records featuring such artists as The Ronettes, The Crystals, The Shirelles, and Martha Reeves and the Vandellas. He also liked the pretty boys—Ricky Nelson and Bobby Vee, the surfer sound of The Beach Boys, and the British invasion by The Beatles and The Dave Clark Five.

Doyle’s musical taste also showed refinement—Lena Horne’s sultry “Stormy Weather” and the jazz of Billie Holiday. In 1964 he purchased his first Barbra Streisand album. Ironically, his first exposure to a gay musician wasn’t positive. “I thought Liberace was rather creepy,” Doyle admits.

He took dance lessons and found dates for school dances, but says his heart wasn’t in it. He already had crushes on male schoolmates, including his best friend.

College Days, Chemical Engineering, and Coming Out

In 1965, Doyle enrolled in nearby Youngstown University to study chemical engineering—a long and rigorous five-year program. During summer breaks, he worked with survey crews and did odd jobs like painting guard rails.

In 1970, his superior scholastic record landed him a job with Eastman Kodak in Rochester, New York, as a chemical engineer. He was tasked with such projects as effectively piping chemicals and ensuring the safety of the gigantic chemical storage vats.

But by 1978, Doyle no longer wanted to contend with the bitter New York winters. He moved southward to Norfolk, Virginia, and found work as a plant engineer.

Coming out was not easy. He thought about homosexuality, and pondered it while reading Blueboy and The Advocate. He was fascinated by Sgt. Leonard Matlovich, who had to fight to keep his job after coming out in 1975 while serving in the Air Force. But Doyle remained closeted.

The 1979 March on Washington

Doyle became involved with a Norfolk gay group that met at the local Unitarian church. There were about 40 members—the sum total of Norfolk’s gay activists. The group published a monthly newspaper, Our Own Community Press. Doyle worked on the paper and soon became editor.

He decided to attend the 1979 March on Washington so he could take photos and write about the event. What he saw changed his life. “It was incredibly empowering—so many gay people in one place at one time, calling out for their rights,” he says.

Eventually, Doyle was laid off from his Norfolk job. He sold his townhouse and took a cross-country trip through the South, visiting and evaluating several cities in order to find a new residence. He wanted a city with moderate winters and an organized gay community.

Doyle spent time in Houston, living at the Lovett Inn, visiting the bars, and getting to know people and the city. Eventually, Houston became his choice for a new home.

Settling into Houston

Doyle began living in Houston in 1981. He joined the gay bowling league, shared a tiny apartment on Garrott Street, and bartended at EJ’s.

He then moved into 1400 Richmond, the gay mecca of 1980s Montrose, and lived there four years. He found a job in the inventory control department at the Design Center and worked there until 1986.

Doyle’s next job was answering phones at a Houston IRS office. “It was high pressure. When one call ended, the next call was immediately routed to us.” His customer skills became obvious, and he was promoted to split his time between correspondence and phones.

In 1987, Doyle moved to a Galleria-area condo while continuing to advance at the IRS job. In 2000, he was the natural choice for a newly created “tax advocate” position. He continued this work until his retirement in 2010.

Music and Radio

During the 1980s, Doyle continued to expand his ’60s girl-group collection. (He believes gay men like these groups because the artists were stylish and they often sang about emotional vulnerability.) Doyle ended up selling most of those records in the 1990s and began collecting only queer music. He networked with queer artists and built a reputation as an expert in the field.

Doyle often called Jimmy Carper on KPFT’s After Hours in the late 1990s, asking him to play queer music. Jack Valinski took notice and invited Doyle to appear on Lesbian & Gay Voices once a month, with a one-hour Queer Music Heritage (QMH) segment. QMH is now in its 14th year on the air.

Doyle has also been one of several co-hosts of Voices since 2000. Additionally, he provides the queer music that Voices plays between segments.

In 2001, Doyle partnered with This Way Out—a popular radio magazine—to co-produce a seven-minute segment entitled Audiofile. This segment showcased three recent CDs by LGBT artists, andwas broadcast for nine years.

In 2010, Doyle began producing OutRadio, a monthly Internet show that features emerging queer artists. The show is now in its fifth year.

Sharing His Treasures

With the rise of the Internet, Doyle created the Queer Music Heritage website (queermusicheritage.com) in 2001, and it has grown to more than 2,000 pages. He continually adds new sections (such as drag music, women’s music, and gay musicals) as interest is shown.

In 2011, Doyle authored an online Queer Music History 101 course that spans queer music from 1926 through 1985. With the rise of college LGBT studies programs, it has been used as a ready-made course that Doyle offers free to schools and individuals.

In 2012, Doyle launched the Houston LGBT History website at houstonlgbthistory.org. It includes photos and audio files of important Houston rallies and events; rare 1970s photos of Houston’s gay bars; Houston Pride celebration logos, themes, marshals, and guides for each year since the first celebration in 1979; and much more.

In 2013, Doyle produced a benefit CD for the Houston Transgender Foundation Building Fund. Entitled House Blend, it features transgender artists.

In 2014, he rolled out the Texas Obituary Project, with scans of more than 5,000 death notices from Texas LGBT publications. Michael Hallock in Dallas sent Doyle an e-mail recently: “I went to the site and could not stop reading. The notices and photos triggered so many memories of people. They will now be remembered for eternity. You are a hero and have given a tremendous gift to all of us who have memories of our friends, long gone.”

In 2014, Doyle also was part of a project team that launched The Banner Project: An Exhibition of Houston LGBT History. Twenty-seven vinyl banner panels, 30 x 65 inches each, feature important points in Houston’s LGBT history. The project debuted at the 2014 Creating Change Conference in Houston. It serves as a “pop-up museum” available for galas and other events, and its companion website is at houstonlgbthistory.org/banner1.html.

Love and Loss

In 1983, Doyle met his first partner, Kim Spradling, at 1400 Richmond. They lived together for a year and a half, and Spradling died of AIDS in 1991.

In 1987 Doyle met his second partner, Wesley Gregson, at the Montrose Mining Company. Nine months later, Gregson died of AIDS at age 29.

In 1995, Doyle met his third partner, Jeff Pierce, in a dance class that the Brazos River Bottom bar offered, using the Rainbow Rangers as teachers. Doyle was a founding member of the dance club and the assistant instructor.

Doyle and Pierce were lovers for the next 12 years. In the third year of their relationship, they exchanged rings. Pierce worked in a shoe store, but wanted to be a teacher. He attended the University of Houston until he earned his degree, and began teaching third graders. His beloved career lasted less than a year; after being diagnosed with cancer, he lost his battle with the disease in 2007.

“You don’t get over it,” Doyle says, “you just get through it.” Even today, it is difficult for Doyle to speak about Pierce. “He was my soul mate. We were so perfectly suited for each other.”

Retiring to The Woodlands

In November 2007, an illegal crystal-meth lab in one of the units at Doyle’s condo complex exploded. While Doyle’s condo suffered only minor smoke damage and his LGBT music collection remained intact, the traumatic episode prompted Doyle to buy a home in The Woodlands in 2008.

Now retired, Doyle says he can “do what I want, when I want.” He appears well on his way to becoming a full-time historian for Houston’s LGBT community.

Doyle shares his house with a pet schnoodle, a schnauzer/poodle mix named Parker. In one room of the house are 30 stuffed toys. Doyle can tell Parker which of the 30 toys to find and bring to him—and Parker gets it right every time.

Community Recognition

Doyle is the recipient of numerous awards for his work, especially with LGBT music. But he considers the sweetest recognition to be his 2014 Houston Male Pride Marshal honor. After the announcement party, he drove to see Pierce’s parents. “We see each other almost every week,” Doyle says. “His father and I drive to a Mexican restaurant, have a margarita on the patio, and then pick up a take-home order.”

Doyle has asked his best friend, Scott Wyatt, who lives in Norfolk, to share the spot next to him on the back of the convertible that will bring him down Westheimer during the 2014 Pride Parade.

Reflecting on his life, Doyle feels blessed. Reflecting on his many history projects, he says: “It’s my gift back to the Texas gay community. I am grateful to be gay and a member of the gay community, and it’s been a very interesting life—one that my radio and history work have much enriched, well beyond what I could have imagined. So to give back what I can in my work is very satisfying.”

Brandon Wolf also writes about the female and ally grand marshals in this issue of OutSmart magazine.