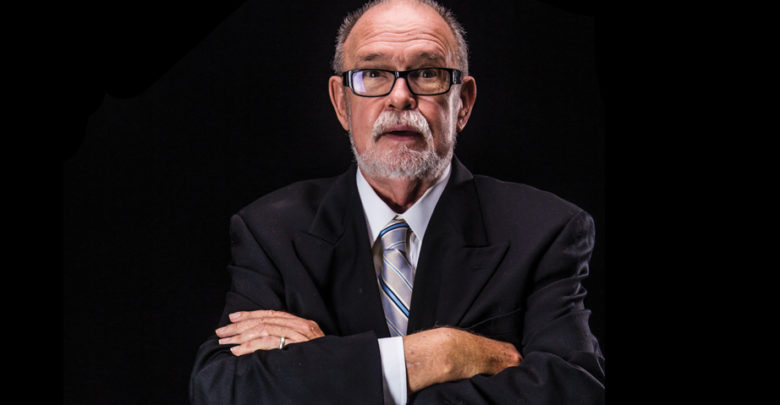

Editor’s Note: A memorial service for Ray Hill will be held at 2 p.m. Sunday, December 2 on the steps of Houston City Hall. More info here.

On November 24, at 6:30 in the evening, the late-autumn sun had just set when Raymond Wayne Hill quietly drew his last breath. Following a remarkable fight, Hill succumbed after a lifelong battle with heart disease.

Houston’s fiercest champion of LGBTQ rights died peacefully in hospice care at Omega House, while enveloped by the love of friends and admirers. With his transition, the 78-year-old took his enormous personality, groundbreaking life, unique brand of courage, and rare sense of humor with him.

Coincidentally, Hill helped launch Omega House in the 1980s. Its sole mission at the time was to care for dying AIDS patients who were often shunned by the larger medical community and abandoned by their families. There had been many nights when Hill stroked a dying young man’s head in the same modest facility that housed his own failing body in the end.

A parade of people visited Hill’s bedside as the curtain slowly fell on his life following his third heart surgery in 20 years in early August. Attorneys, teachers, politicians, sex workers, recovering addicts, and journalists sat with Hill as he soaked up their love, and rewarded them with his stories. Those stories gradually became shorter in recent weeks as Hill’s energy waned and his voice softened to a whisper. Even mayor Sylvester Turner spent a few private moments with Hill, tearing up as he held the activist’s hand.

To say Ray Hill will be missed doesn’t begin to express the sadness in Houston’s LGBTQ community. With his passing, Houston’s own “royal” in the fight for LGBTQ equality fades into history.

On the night of Hill’s death, Mayor Turner released a statement.

“Ray Hill, my friend and warrior, has passed,” Turner said. “Fighting for gay rights, human rights, criminal-justice reforms, Ray was on the frontline and helped pave the way for many others to follow. He was authentic, committed, and respected.

“Ray had a heart for justice, equality, and acceptance for decades, and he followed his heart into the streets, courtrooms, City Council chambers, legislative hearing rooms, jails, prisons, and radio stations of our city and state, advocating for his causes well before they became popular. I’m one of many people who agreed with him about his important causes. But such positions are relatively easy to take and express now, [decades after] Ray blazed the trail.

“Rest in peace, Ray Hill,” Turner concluded.

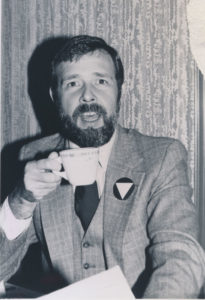

The Beginning

Hill was born in 1940 at Baptist Memorial Hospital in downtown Houston. His parents, who lived in the working-class community of the Heights, were labor organizers. He later said they paved the way for his dogged pursuit of civil rights and LGBTQ equality.

Hill came out to his family in 1958 while attending Galena Park High School, where he was quarterback for the varsity football team. “When I told my mother I was gay, she took a drag on her cigarette, then a sip of her coffee. Finally, she said, ‘Well, that’s a relief,’” Hill later recalled.

“A relief?” Hill responded to his mother.

“We don’t expect that response from parents today, much less parents at that time,” he said later.

“Well, we noticed you dress better than other boys,” she continued, “and with you playing football and all, we were afraid you were going to grow up to be a Republican.”

Life after high school was rife with temptation for Hill. He claimed that he partied with Truman Capote. (“Truman was always knee-crawlin’ drunk. Always,” Hill would say.) He also insisted that he could often be seen on the arm of Tennessee Williams.

But as Hill’s tastes for the finer things developed, so did his appetite for acquiring them by any means available. He began breaking into galleries at night—ones where he knew the inventory was insured. “I stole a whole lot of stuff. Jewelry, antiques, art—you know, stuff queers really like,” Hill said later.

In 1971, his life as a criminal screeched to a halt. He was serving time in a California jail for unrelated crimes when he was extradited to Texas for trial. None other than Marvin Zindler (who was on his “Harris County sheriff’s stage” at the time), showed up to collect Hill.

“When Zindler realized he knew my family, he pulled the cop car over and told me to get out. First, he removed my leg irons and handcuffs, then he threw me the car keys and made me drive all the way back to Houston while he slept in the back of the car, farting and snoring the whole way,” Hill later said.

With his return to Texas, Hill was tried, convicted, and sentenced to prison for 160 years. He quickly launched an appeal of the sentence and won. The 160-year incarceration was shortened to eight, and in 1975 he was released early—a reward for being a model inmate.

The Middle

Hill’s experiences in prison opened his eyes to the entire, putrid Texas Department of Criminal Justice. From the moment he was released, Hill became one of the state’s most vocal proponents of prison reform. He would also share what he learned on the inside with anyone in need. In fact, Hill gave Martha Stewart “going-to-prison lessons” prior to her incarceration in 2004. The two would meet on Skype, and Hill would absorb the domestic diva’s attention for hours on end.

Always striving to improve life for the community, Hill co-founded Houston’s first LGBTQ-rights organization with two friends. In the early 1970s, he began working at Houston’s only publicly funded radio station, KPFT (which he co-founded in 1968). During his regular call-in show on LGBTQ issues, Hill received calls from listeners who threatened to kill him—live, on the air. He would respond by giving the caller directions to the station.

In 1978, Hill organized Town Meeting I, a gathering of 4,000 people at the Astro Arena during Houston’s first LGBTQ Pride month. Town Meeting I served as a catalyst for the formation of many LGBTQ organizations, including what is now called the Montrose Center.

In 1979, Hill helped organize the National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, the first march of its kind in the U.S. He worked with San Francisco city supervisor Harvey Milk to pull off the massive event.

“We only got about 80,000 people to DC, but no one had ever seen that many queers in one pile in history,” Hill once said.

Houston filmmaker Jarrod Gullett, who produced a 2015 documentary about Hill’s life, acknowledged that he had his detractors.

“Some people resented the way Ray could, and often did, suck all the oxygen out of a room,” Gullett said. “What people didn’t understand is that Ray would do that on purpose. If a group of people who should have been working together were divided, Ray would stir up trouble. He would unite them by making all of them mad at him instead.”

Tony Carroll, the late gay psychotherapist and community leader, explained to OutSmart in 2015 that there were those in Houston’s LGBTQ community who wished to be as loud as Hill was, but couldn’t match his courage.

“Many of us were stuck—paralyzed—because of society,” Carroll said. “We always supported Ray in what he did, but we didn’t have the luxury of the doing the same.

“Some of us were business owners, some were government workers or teachers, and others were professionals with years of higher education,” Carroll added. “To be vocal and visible would have cost us our patrons, students, and livelihoods. Ray never had to be concerned with losing everything, because he never had anything to lose.”

Gullett said he believes Hill lived most of his life below the poverty line for a reason.

“Having little to lose set him free do the work he needed to do, to speak truth to power. It was more important to Ray to remain untethered [rather] than comfortable.”

The End

Hill’s experiences have been the subject of several documentaries. His long-running KPFT radio show dealing with Texas prison issues was the subject of a 2005 film, Citizen Provocateur: Ray Hill’s Texas Prison Show. He is also a featured character in The Guy with the Knife, released in 2015, about the murder of gay Houstonian Paul Broussard. After helping police capture Broussard’s killers, Hill famously fought for the release of one of them, Jon Buice.

Gullett’s documentary, The Trouble with Ray, launched as a 22-minute work. However, Gullett and art director Travis Johns (of Proud Pony International) had little choice but to heed numerous pleas to make it longer. And Hill’s life provided ample fodder. The longer version will be released sometime in 2019 and is aptly titled Loud Mouth Queer.

What compelled these filmmakers to tell the story of Ray Hill?

“An activist doesn’t spend 50 years fighting for LGBTQ equality in the land of steers and queers just to give up,” Johns stated. “Ray wanted to pass the torch and ignite the next generation. He was a great choice for keeping the wheels moving, because he was in the thick of the movement from the beginning.”

In Hill’s final days, it became clear that the battles he fought before the U.S. Supreme Court were his proudest moments. In 1987, Hill was the plaintiff in The City of Houston v. Hill, The lawsuit challenging the City ordinance that made it illegal to “interrupt” police officers performing their duties. The Supreme Court ruled in Hill’s favor, saying the ordinance violated the First Amendment. That court decision altered law-enforcement practices across the nation.

Hill was also heavily involved in Lawrence v. Texas, the Supreme Court case that overturned anti-gay sodomy laws nationwide in 2003.

On December 2, a memorial service for Hill will be held on the steps of Houston City Hall. Mayor Annise Parker, whom Hill charged with organizing the event, served as keynote speaker. Hill requested six pall bearers—two cops, two ex-cons, and two members of AA.

Hill’s ashes will be scattered in a family cemetery in Flo, Texas. He made certain to acquire a gravestone for the site in advance of his transition, or “journey across the River Styx,” as he referred to his approaching death.

In keeping with his proudest achievement, the gravestone simply states:

Ray Hill 1940–2018

U.S. Supreme Court decision – Houston v. Hill (107 S. Ct. 2502)

Its brevity makes sense. It would take hundreds of headstones to list the rest of Hill’s contributions to the nation’s civil-rights history.

‘The River Styx’

In the final few months of Hill’s life, destiny sent him a professional “Death Doula,” or end-of-life midwife to help him transition. Within a short time, nurse Amy Morales and Hill became inseparable.

Hill never shied from speaking of his impending death, often referring to it as “crossing the River Styx.” Morales spent hours with Hill discussing the subject.

The story of the River Styx is a tale that comes from Greek mythology. Styx was believed to be the river that served as the barrier separating the world of the living from the world of the dead. In order to cross the River Styx, a dead person had to pay a fee to the ferryman. Those who couldn’t pay the fee would have to swim, and very few made it to the other side.

On the night of November 23, Morales kept her vigil at Hill’s bedside. “I didn’t know that would be Ray’s last full night on this Earth,” she remembers.

“When I got home that morning, I found myself with an overwhelming desire to cry and an inability to sleep,” she adds. “Ray was separating from this realm, and I could feel it happening.

“When I arrived the next morning, I rubbed Rays’ hands, expressing my love and gratitude to him,” Morales says. “He was unresponsive. I started to clean up his belongings without realizing why. When I found a gold-colored plastic coin that someone brought to help him scratch lottery tickets, it dawned on me: Ray was close to the River Styx.

“I thought he would appreciate me humoring him with a kind, albeit silly, gesture,” she concludes. “I fixed the coin to his hospital gown over his heart with tape and labeled it ‘For the Ferryman.’ I wanted to be sure he had the passage fee. The chip was still there when he drew his last breath.”

Morales knew her friend well, and that golden coin attached to his gown is the sort of gesture Hill would have savored.

This article appears in the December 2018 edition of OutSmart magazine.