Wherefore Art Thou, My Community?

The death of the local gay, lesbian, bisexual, transgender scene is greatly exaggerated, a senior activist, observer, and rabble-rouser writes. The community continues to evolve, as always.

By Ray Hill

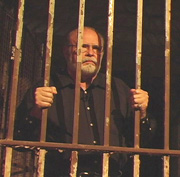

Photo illustrations by Yvonne Feece

For the readers who have never heard of me, I am the old man of our Houston movement toward equality for lesbian, gay, transgender, and bisexual or otherwise queer folks. I came out to my family and at Galena Park High School in 1958. I began writing articles challenging antigay prejudice in 1966 and began organizing and appearing in the media in 1968. With a few years off for bad behavior (I went to prison in 1970 and did not return until 1975) I have worked full time seeking to build and support our community.

Recently, I have had a couple of conversations in which people have complained that Houston “…did not have a gay community.” This article is to address that idea and enjoin the help of the reader to support the concept offering the benefits of a strong GLBT community.

The first use of the term “gay community” in my experience meant the part of town where the bars were. At first, for me (in the 1950s) that was on Almeda Street from the Pine Lounge at Holman to Ken Ray’s Red Devil Lounge at Southmore. The term would later refer to lower Westheimer and then encompass most of Montrose. There were (and still are) bars elsewhere in the city, but the term referred to the concentration of bar locations.

The variety of queer folk in that era had no particular feeling of connection to each other. More accurately, we had a kind of distaste for each other. Rarely would one hear anything positive about other GLBT people in conversation. Most of us had a circle of friends but felt nothing in common with those outside our circle. There was the A Group who looked down on the B Group, the butches who looked down on the femmes, the men who thought little of the women, and the women who felt no association with the men, as well as divisions along economic, racial, and ethnic lines. The only thing we had in common was the prejudice against us held by everyone else in society and the fear that a single arrest or anonymous phone call would bring our lives and careers crashing down around us.

Most of us lived in closets at work or school and in the neighborhoods where we lived and even denied who we were to our families. Unmarried men with prematurely orange hair insisted everyone thought they were straight. To advance in some jobs one had to be married, leaving whole neighborhoods of frustrated wives seeking adventure elsewhere, because their own beds were pretty boring.

It was GLBT people who reported other GLBT people in the workplace, seeking advancement over them. We did not like ourselves and thought even less of others like us. The term “gay pride” had not yet been coined nor was there any need of it. Since I was out, I could see people jaywalking on downtown streets to keep from being seen with me in public.

And Then…

Anita Bryant came to town on June 16, 1977, and everything changed. Overnight, something was different, very different. We gathered to demonstrate against her appearance, because we were tired of the fear and angry because of the attacks. We had never actually seen each other as brave souls willing to stand up for what we knew was right. The turnout (about 12,000) was a product of effective organization and the fact that it was the right time for us to emerge in a changing society. Our movement had been predicated by the women’s movement, the civil rights movement, the free speech movement, and a movement to end the war in Vietnam. Many of us were veterans of those causes, but this time the effort was for us and our equality. That night the term “gay community” changed from “where the bars are” to “a group of people with common goals and aspirations.”

I am an organizer. My parents were labor organizers. I had read the history of movements and knew that we could not lose this spirit that Anita Bryant had given us. We had the political caucus, Metropolitan Community Church, women’s softball league, and the bars, but no other institutions to sustain a community. Movements can be nurtured and developed in bars. The American independence movement was birthed in taverns in the then-British Colonies. But our bars were different. They were designed for anonymous cruising, not meaningful discourse. We needed new institutions. I called for Houston Town Meeting I. Out of that event came many of the organizations, institutions, and services that have sustained our community since. Just check and see how many things we now take for granted that were founded in 1978 at that meeting or soon after. It is really quite impressive.

Responding Together

Even before the scientists decided on the term Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome in 1982, Houston had organized the Kaposi Sarcoma Committee, in 1980, because we were a community of people with a problem that needed our attention. We acted like a community and responded as a community. That group became the KS/AIDS Foundation, which is now AIDS Foundation Houston. Soon there was ACT-UP and several other HIV/AIDS service groups and institutions. Each served its purpose and those that were well organized still function as needed—among these are The Center for AIDS and Bering Omega Community Services Center, which includes the Bering Dental Clinic and Omega House, the hospice.

When Paul Broussard was killed and the police would not investigate the crime, I went to a then-active Queer Nation for help. We responded as a community in peril. Another community group, Q-Patrol, revived an earlier Montrose Patrol idea and helped make the neighborhood a safer place until it died for lack of capable leadership.

I have seen us as a community respond to crisis together. I see many institutions: Pride Houston, AIDS Foundation Houston, Montrose Counseling Center, Houston GLBT Political Caucus, Legacy Community Health Services, Houston GLBT Community Center, numerous churches, sports associations, and leagues, the Center for AIDS, LEAP, Houston Transgender Unity Committee (and the several transgender groups it reaches), Stonewall Lawyers Association of Greater Houston, Greater Houston GLBT Chamber of Commerce, SCALE (the coalition of AIDS service groups that concentrates on outreach and education), and many more.

If you do not think there is a community here, you are not looking very closely. But as Harvey Milk said when asked about the gay Pride turnout in San Francisco, “Never enough, never enough.” Could we organize a response to violence as we did when Paul Broussard was killed? I don’t think so. There is no Queer Nation and no effective short-term communication vehicles like we had then. Do all groups work toward our unity? No, the Human Rights Campaign seems determined to divide us into unapproved and approved groups deserving of equality. Are our young people aware of the history of our struggle? No, but that is not as important as their willingness to defend what has been achieved for their benefit. What about those who worked in the struggle? Having watched our community evolve and grow, we can serve as a source of historical perspective and advice for the newer generations. And we have the memories. Oh, the memories.

Ray Hill is the longtime activist for GLBT and prisoner rights and a monologuist whose works include Ray Hill in Love, Ray Hill & the Sex Police, and Queer Like Ray Hill. His website is www.rayhill.info. Hill contributed the article “Three Years of Freedom,” about the anniversary of the historic Lawrence v. Texas decision, to the June 2006 OutSmart.

Hill on Film

At the recent Tacoma Film Festival, Ray Hill’s Prison Show, the Brian Huberman-directed documentary about Hill and his Friday-night KPFT radio program for inmates and their loved ones, was a top-10 pick of executive director Philip Cowan. Hill, who attended the October 9 screening for a post-film conversation, reports that the film ranked ninth of 200 entries in an audience-appreciation poll.

Another documentary involving Hill, this one recounting the events of the 1991 murder of Paul Broussard and his assailants, including Jon Buice (who recently lost his latest bid for parole and remains in prison), now has a title: Where Is Heaven? Alison Armstrong, a director affiliated with the Canadian television network CBC, is completing this film.

Photo caption: Ray Hill traveled to Washington state for the screening of the documentary Ray Hill’s Prison Show at the Tacoma Film Festival. Bond Huberman, editor of the Tacoma magazine City Arts joined Hill for the screening. She is the daughter of the documentary director, Brian Huberman.