‘Thomas’ Turns Twenty

Thomas Street Health Center celebrates two decades of service.

By Rich Arenschieldt

Photos by Yvonne Feece

See also: World AIDS Day in Houston

Evoking a bygone era, two palm trees tower over a 1920s Gatsby-esque building. This registered historic structure, completely untouched on the outside, inside has been replicating its success as one of the nation’s most important bastions of HIV-related care and research.

Celebrating its 20th anniversary, Thomas Street Health Center (TSHC) is the Harris County Hospital District’s (HCHD) freestanding HIV/AIDS treatment facility, providing medical and support services to residents of Harris County with HIV/AIDS.?Two decades of caring for individuals facing serious health issues has put TSHC at the forefront of the epidemic. Countless staff and volunteers have assisted patients since the clinic opened on May 1, 1989. Twenty years ago a group of medical musketeers embarked on an incredible adventure in medicine, one that continues today.

“TSHC started as a hospital for the employees of the Southern Pacific Railroad,” according to original staff nurse, Jerry Boice, RN, BSN, ACRN. “It had been used in various capacities before HCHD gained possession of it.”

The acquisition of TSHC was prescient—it occurred as the number of HIV cases in Harris County began to rise and as other facilities treating patients were shutting down. “The Institute for Immunological Disorders was closing and we knew that there would be an influx of patients into HCHD,” Boice said. “Combined with the patients already at the Chest Clinic at Lyndon B. Johnson Hospital and the Infectious Disease Clinic at Ben Taub General Hospital, it was clear that the public health-care system would soon be overwhelmed with HIV-positive patients. Lois Jean Moore [then CEO of HCHD] was a wonderful advocate for providing medical care to people with HIV. Under her leadership HCHD chose the clinic, which, at that time, was centrally located to patients.”

Dr. Thomas R. Cate, retired professor at Baylor College of Medicine, was one of the first physicians to see patients at TSHC. “With the expansion of the epidemic, we knew that we had to have a dedicated, local facility to treat patients,” he said. As the clinic’s first medical director, Cate reports that he “just kind of fell into the job. Very shortly after coming to TSHC, I was spending the majority of my time there.”

According to Cate, “Clinics like TSHC were somewhat rare. There were others, especially on the east and west coasts, at the epicenters of the epidemic. TSHC was one of the earliest facilities in the south and in Texas.”

With limited medications in their armamentarium, TSHC staff often found themselves in medically uncharted territory. Patients were despondent. AZT, the only medication indicated for controlling HIV infection, had been approved in 1987, and the CDC had just issued treatment guidelines for the treatment of PCP (Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia), a major cause of HIV-related mortality. “At that time I was working with other doctors, including my colleague, Dr. Robert Awe. All of us were seeing a lot of opportunistic manifestations of HIV, especially pulmonary infections.” Undeterred, Cate and others persisted.

Early days at TSHC were simultaneously challenging and invigorating for the sparse staff. At that time the clinic looked nothing like its present-day incarnation. According to Boice, “It was dark, dingy, and we only used the first two floors. We had a handful of docs and about 350 patients. Ninety percent of them were gay white males, some were intravenous drug users, and just a handful were women.”

One of those original patients was David Douhunt, diagnosed with HIV in 1989 and currently a TSHC volunteer patient mentor. “I was one of the first people there when they opened the doors. I remember that the place was like a museum—a dusty old hospital. It looked like something out of an old movie, but we didn’t care. Patients were so happy to have their own clinic; this was a dream come true for us. Many of us had received our care at other clinics throughout HCHD. We used to get frustrated, because prior to TSHC, people would always ask us why we had medical appointments, and we didn’t want to disclose our status.”

Stigma, ignorance, and secrecy abounded. There were still many impediments to caring for patients who were part of a burgeoning, behaviorally centered epidemic. “There was still a great deal of fear associated with treating TSHC patients, even among medical professionals,” Boice recalls. “We experienced a lot of stigma from others who couldn’t understand why someone would choose to work at TSHC. Every professional who was at the clinic volunteered for their jobs there,” Boice said. We educated medical staff and residents about transmission issues.

This sentiment is echoed by Dr. Cate. “The staff was in many ways invigorated by the challenges that we faced on a daily basis. Over time we put systems in place that monitored patients and helped them to stay well. The patients were very appreciative of our efforts and were very compliant with medication and appointments. In spite of the difficult circumstances, there were many people we really enjoyed taking care of.”

Though not public knowledge, some of the TSHC staff had a very close connection with patients in the clinic. According to Boice, “Several of the staff were part of the GLBT community. They saw what was happening to people they cared about and wanted to be part of a solution for the epidemic.”

As utilization of TSHC increased, it became clear to the staff that the existing “museum” they inhabited needed a major makeover. “In the early ’90s we obtained a large federal grant to completely redo the interior of the clinic,” Boice stated. “They started the reconstruction from the 4th floor down, demolishing everything to the exterior walls. When the top two floors were completed, we moved up there, and they began construction on the two bottom floors. It was chaotic, but as the employees witnessed the transformation, we became very excited about working in a brand-new clinic. Also, patient care improved dramatically as the result of this reconstruction. There was now space for physical therapy, medical records, social workers, case managers, radiology, and pharmacy. We were also able to house additional medical staff. ”

“When Dr. Cate informed us that we would have access to expanded services as the result of reconstruction and enlarging of the clinic, that was a huge help to us,” patient Douhunt said, “especially with regard to mental-health issues. Having a psychiatrist here enabled us to deal with some of the issues that contributed to our becoming HIV positive. We were finally able to address the emotional impact of HIV on us and our families. Also, when case managers came to help us to get housing and other services, it allowed us to live more stable lives and stay healthy. The word ‘family’ took on a new meaning—we would look forward to seeing other patients—the camaraderie throughout the clinic was wonderful. Patients motivated each other.”

With the advent of Ryan White funding in 1990, money was allocated for a Volunteer Program, sponsored by the People With AIDS Coalition of Houston. “Lynn Pannill [then executive director] facilitated the creation of that program,” Douhunt said. “This was a big turning point for patients. Volunteers took care of everyone, and organizations like the Colt 45’s and other GLBT groups also provided lots of help to us.”

While this support may seem ancillary in nature, in the early ’90s it was crucial. According to Douhunt, “it was beneficial in many ways, but most of all it helped people to stay away from activities that were harmful to them—abusing drugs and alcohol.”

“Clinic staff provided much more than medical care,” Boice remembers. “We were able to empathize with their situations. We did take the time to sit and listen to them and try to give them hope. We did some research, but it was limited. We just didn’t have many drugs in the pipeline to work with.”

With any illness, when a dedicated group of clinicians focuses on a disease process, they inevitably make progress toward a solution, if only incrementally. “After a period of seeing patients with the same symptoms, we began to notice trends and similarities,” Dr. Cate reported. “As our knowledge evolved, we began to take care of patients earlier. When we stopped having to put out so many fires, things became a little more manageable. Also, as time progressed, patients became more alert to what an HIV diagnosis meant; they realized quickly that they needed to take care of themselves.”

“One of the things I was proud to see,” Dr. Cate remembers, “was that, after a period of time, the clinic was able to provide not just care in response to emergent situations, but care that helped us to become pretty darn good at managing HIV infection and its complications. At that time, this was the best we could hope for. Patients evolved with the clinic. As we provided better care, the patients became more involved in their own health outcomes.”

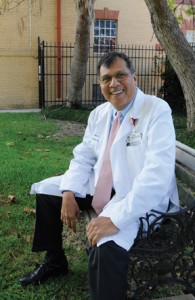

Today, the man in charge as medical director is physician Thomas P. Giordano, assistant professor at Baylor College of Medicine. Like his predecessors, Giordano shares the same traits of commitment and inquisitiveness. “TSHC has always been interesting to me because of the breadth and diversity of patients—all ages, genders, and risk factors for infection are seen here. I came to Houston to train in infectious disease precisely because there was a large HIV-positive population, many of whom were treated in a single clinic. As a physician, TSHC provided a great opportunity to care for people with HIV.”

In addition to providing clinical care, Giordano, like most of the TSHC medical staff, participates in a variety of research projects to improve outcomes. “One of our milestones was the clinic’s substantial involvement in the 2002 SMART [Strategies for the Management of Anti-Retroviral Therapy] study, a collaborative effort between UT, Baylor, the Veteran’s Administration, and others.” This worldwide study, funded by the National Institutes of Health, was the largest clinical trial of any infectious disease and was used to answer crucial questions about long-term management of HIV. “We were heavily involved,” Giordano said. “In fact, among all the centers that participated, only the country of France enrolled more individuals in this study than we did at TSHC.”

Research continues to play an important role within the clinic’s medical milieu. Recently, Giordano and others have concentrated their research on how to use existing tools more effectively to help manage disease. A continuing question for Giordano is, “How do we get medications to patients, and how do we keep them connected to the clinic to maximize positive health outcomes?”

Given that the clinic serves as the medical safety net for half of the uninsured HIV-positive patients in Harris County, the public health ramifications of staying on medication and being healthy are economically and epidemiologically important.

“We have made incredible progress in terms of the efficiency and effectiveness with which we deliver care,” Giorodano said. “Today TSHC is comparable to any major HIV specialty clinic in the nation. Other clinic directors who visit us are very impressed with the physical plant, as well as the comprehensive care that we provide.”

“We are very lucky to have so many physicians who are doing research on national and international projects,” says Pete Rodriguez, RN, BSN, ACRN, the director of HIV services at TSHC. “They are our eyes and ears that determine which projects we undertake.”

TSHC is known for innovative treatment. “Because our physicians are so involved, we are able to make changes to treatments as soon as they become available. We try to stay very current on what is happening with our patients.”

Rodriguez is also very concerned about adherence to medication and care. “Our research also involves patient mentors who are trained to work with patients and guide them through the clinic.” They also have had a lot of input into how research concepts are communicated effectively to patients clinic-wide.”

Seeking to move beyond its historic façade, TSHC has implemented Routine Universal Screening for HIV (RUSH), whereby more than 25,000 patients accessing HCHD emergency centers have been screened for HIV. “This follows the established CDC guidelines that seek to include HIV testing as a routine part of medical care,” Rodriguez said.

Medical Director Giordano and others express sincere optimism for the future. “With proper treatment and lots of effort from patients, HIV has become a manageable infection. Patients now have many options, and as a clinician that’s very exciting to me. Currently, medical practice is built around episodic problem solving. Eventually, we will need to transition TSHC to treat chronic disease and keep people in care.”

Volunteer Patient Mentor Douhunt is still concerned about the 50 newly diagnosed individuals that arrive at TSCH monthly. “In spite of all of the education that we have done, we still see many younger people; we continue to battle addiction issues and we continue to combat stigma. As a mentor I tell my story and share how my behavior after I became positive has helped me to survive. I didn’t think I would be here after 20 years. All of the good health I have, I owe to the medical staff of TSHC. Just by being here in Houston, Thomas Street Health Center saves lives.”

Rich Arenschieldt wrote about the Ryan White CARE Act in the October issue of OutSmart.

____________________

World AIDS Day in Houston

Annually commemorated worldwide, World AIDS Day highlights the progress made in the battle against HIV/AIDS and serves as a reminder of how much still needs to be accomplished in the fight against the disease. This year, World AIDS Day is being recognized in Houston with the following events.

HIV Testing. Free HIV testing, with no gold card or donation required or requested. 9 a.m.–1 p.m. daily. HCHD Thomas Street Clinic, 2015 Thomas St. 713/873-4157 • 713/873-4026.

HIV Testing. Legacy Community Health Services offers free confidential rapid HIV testing using the OraQuick-Advance collection method with results available within 20 minutes. MONDAYS: All Star News and Video Emporium, 3415 Katy Frwy. 4–8 p.m.; George Sports Bar, 617 Fairview, 6–10 p.m. • TUESDAYS: 611 Hyde Park Pub, 611 Hyde Park, 4–8 p.m.; Midtown Spa, 3100 Fannin St., 4–8 p.m. • WEDNESDAYS: Club Houston, 2205 Fannin St., 8 p.m.–12 a.m.; EJ’s, 2517 Ralph, 10 p.m.–1 a.m. • FRIDAYS: Midtown Spa, 3100 Fannin St., 5–9 p.m.; EJ’s, 2517 Ralph St., 10 p.m.–1 a.m. Free, confidential syphilis testing is also offered. HIV and syphilis testing is offered at 215 Westheimer Rd., Monday through Thursday, 11 a.m.–7 p.m. and Friday, 11 a.m.–5 p.m. 713/830-3070.

HIV Testing. Planned Parenthood offers daily free anonymous or confidential testing at clinic locations throughout the area. To speak with an HIV counselor, call 1/800-230-PLAN. Dickinson: 281/337-7725. Fannin St.: 713/831-6543. FM1960: 281/587-8081. Greenspoint: 281/445-4553. Huntsville: 936/295-6396. Lufkin: 936/634-8446, ext. 223. Rosenberg: 281/342-3950. Stafford: 281/494-9848.

Illuminations Project, an annual music, dance, and drag showcase, features performers from the Houston area helping to bring awareness to AIDS. Hope Stone, Houston Metropolitan Dance Company, City Ballet of Houston, Regina Dane, Lone Star Lariats, Psophonia Dance Company, Dance of Asia America, Uptown Dance Company, Kimberly Anne O’Neil, Second Generation Dance Company, Clay Hardy, and Houston Fly Boys perform. Nov. 11, 7:30 p.m. Hobby Center for the Performing Arts Zilkha Hall, 800 Bagby St. $35. Benefits Montrose Counseling Center and Gulf Coast Archive Museum. Illuminationsproject.org.

AIDS Foundation Houston’s 2009 World AIDS Day Luncheon honors PWA Holiday Charities with its Shelby Hodge Vision Award, which recognizes a community member’s commitment and perseverance to improving the lives of AFH clients and their families. For more than 20 years, PWAHC has consistently demonstrated compassion for those living with HIV/AIDS and dedication to increasing the quality of their lives.

“The work of PWA Holiday Charities makes life better for our HIV positive brothers and sisters,” said AFH chief executive officer, Kelly A. McCann. “For that reason, we believe PWAHC is duly deserving of this year’s Shelby Hodge Vision Award.”

Chevron Corporation being honored for its dedication and long-standing support of AFH. Presented by Chevron. Dec. 1, 11:30 a.m. Benefits AIDS Foundation Houston. Four Seasons Houston, 1300 Lamar St. 713/623-6796, ext. 278. aidshelp.org. (See AIDS Watch, page 18.)

Artists from the Healing Arts Outreach Group, a program of Art League Houston led by artist Kermit Eisenhut, display their works in commemoration of World AIDS Day. Some of the pieces of art on displays may be for sale. Dec. 1, noon–8 p.m. Houston GLBT Community Center, 3400 Montrose Blvd., Suite 207. HoustonGLBTCenter@gmail.com.

Bethel Church UCC observes World AIDS Day with a bilingual service of remembrance. The service is being hosted in partnership with other local organizations, including League of United Latin American Citizens and the Houston GLBT Community Center. Dec. 5, 6:30 p.m. 1107 Shepherd Dr. bethelhouston.org • 713/861-6670.

Resurrection MCC and its community partners present Community World AIDS Day Service, reflecting on how HIV and AIDS affect friends, family, community and world. Presented by the Affirming Ministerial Alliance of Greater Houston. Dec. 6, 6 p.m. Resurrection MCC, 2025 W. 11th St. resurrectionmcc.org • 713/861-9149.