Secret Agent

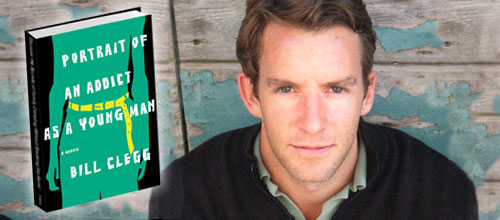

Super agent Bill Clegg was a literati golden boy with hot clients, good looks, a loving partner—and a secret life as a self-destructive crack addict on a fast descent. Steven Foster talks with the agent-turned-author who returned from the wreckage of his charmed life to become a writer as famous as those he represents…

Super agent Bill Clegg was a literati golden boy with hot clients, good looks, a loving partner—and a secret life as a self-destructive crack addict on a fast descent. Steven Foster talks with the agent-turned-author who returned from the wreckage of his charmed life to become a writer as famous as those he represents…

By Steven Foster • Photo by Charles Runnette

If Bill Clegg didn’t exist, some writer would make him up.

Slate eyes, wavy blond hair, cleft chin—Clegg is drawn with such stock-character, all-American good looks that he could have been a model for A&F or, now pushing 40, at least J Crew. But Clegg wasn’t just your average himbo, nor was he born with a silver spoon in his mouth. What Clegg was was gifted, and sharp. With a talent scout’s sixth sense, an editor’s scrupulous gaze, and a nurturing, encouraging demeanor, Clegg took to publishing and became a super agent who attracted and retained some of the most respected writers of the last two decades—celebrated scribes like Nicole Krauss (Man Walks into a Room), Rivka Galchan (Atmospheric Disturbances), and part-time Houstonian Nick Flynn (Another Bullshit Night in Suck City). Such a roster allowed him to break free from the agency construct and open his own boutique with business partner Sarah Burnes. His personal partner was a successful independent filmmaker, and together they tossed glamorous fêtes in their One Fifth Avenue pad. All outward appearances pointed to a young man at the top of his game—a prince and powerbroker enjoying the epitome of success.

Don’t judge the book by its cover.

Inside, Clegg was a tortured jangle of suicidal insecurity, narcissistic need, buried humiliation, and sexual neurosis. He kept this pack of psychological wolves at bay with a bank-breaking, eventually body-ravaging crack habit, vodka jones, and possible/probable sex addiction that he actually believed was manageable. And for a shocking amount of time, he did manage the madness. The façade was so elegantly constructed, this front so perfectly maintained, that when everything came crashing down, the fall was so spectacular it read like a twist from a Publisher’s Weekly pick. He abandoned his business partner via e-mail when she was six months pregnant. He left his stellar stable of writers in the collective lurch, forcing them to scramble for representation just as the book business was bottoming out. He burned through $70,000 paying for hotel suites, Brazilian rentboys, room service vodka by the magnum, and snowstorms of crack. It was so shocking, the Page Six crowd would have fainted if their collective tongues weren’t so busy wagging about the dramatic flameout of their golden boy.

The documentation of that vanishing act became Clegg’s memoir, Portrait of an Addict as a Young Man. (Lindsay Lohan, meet your prison reading material.) For addiction memoir—itself an entire subgenre in publishing—the book makes the surprising choice to ignore the standard agonizing detox chapter and subsequent feel-good recovery denouement. Instead, Portrait is a visceral chronology of a harrowing freefall, told in language that is concise and precise, with telegraphic sentences—dispatches from a junkie’s racing mind. It’s a riveting read where tiny little shard sentences, like so many pieces from a broken crack stem, stab with piercing addict need. The only respite in the barrage of penned agony is the exquisitely detailed euphoria of drug rush. Clegg makes crystalline clear the simultaneous allure and eventual agony of drugs with the book’s near-brilliant opening line:

I can’t leave and there isn’t enough.

While a critical smash, Portrait has failed to catch fire, sales-wise, despite a media blitz that blanketed every media outlet from the New York Times and NPR to The Today Show and Vogue, complete with photographs shot by Norman Jean Roy and love letters by famed ’80s cokehead Jay McInerny. Perhaps in these times, it’s hard to feel empathy for someone who had everything and set fire to it all with a crack pipe in a suite at the Gansevoort. Maybe it’s post-James Frey wariness when it comes to first-person tales of substance abuse. Critics may adore it, but Joe Public has been practically vitriolic. More than one Data Lounge lizard warns a fellow poster who admits a desire to bed Clegg to “be sure to wear a condom, you just know he’s got AIDS.” Fellow agent and wannabe writer—er, blogger—Erin Hosler hisses that Clegg comes off as “the very healthy, very handsome preppy power bottom that he was, is.” Bitter homophobe party? Your table is ready.

Whatever the reason for the venom, Clegg appears more than able to take it. He’s clean and sober, fit and famous, and has regained almost all of his previous clients in his new gig at William Morris Endeavor. His next literary effort, tentatively titled 90 Days, is in the same pipeline (that’s pipeline, not crack pipe) as his clients’ books. Not a bad recovery for someone who once had to add notches to his belt with an awl as he wasted away, literally consumed by addiction.

Steven Foster: You’ve repped some of the most talented contemporary writers in the literary world. Rivka Galchan, Nick Flynn, Susan Choi. Who’s one of your first authors you signed?

Bill Clegg: David Gilbert. The first short story I ever sold was to The New Yorker, a story of his called “Graffiti,” which is a little masterpiece.

How old were you?

23? 24?

How’d that feel?

It felt magical, actually. And very soon after I auctioned off his short-story collection and novel. All of the great publishing houses in New York were after it. It was clearly selling the story that brought attention to him and his work, and I had a very strong sense of it being a sort of sacred privilege—which sounds like an overstatement, but it genuinely felt that way.

Were you using at the time?

At that point I was periodically using cocaine. Certainly drinking heavily every night. And there were friends of mine from college who were in New York, and a few [more] friends, who did coke. But there wasn’t that much around. It wasn’t like in college where it was that present. And I would smoke pot on weekends, but I hadn’t yet tried crack. That would happen when I was 25.

A lot of clients didn’t speak to you after the implosion of your agency, but you gained many of them back after you sobered up, correct?

Yes.

Who didn’t come back that you wished would have?

When I came back to work, I didn’t feel it was my responsibility to be in touch with those writers. I felt like I just had to go to work, show up to work regularly, find other writers, and hope that just my being here would attract people in some way. And not that many people were attracted. It was not a very attractive option for a lot of people. [Laughs] Jean Stein sort of disengaged from her current agent and appointed me her agent. Jean wrote Edie, about Edie Sedgwick, so right away I had one client. It was very moving to me. And when I went back to work, there were a few articles about that, so people who might not have known found out. And some of my writers got back in touch with me, at least to see me again and have lunch. And several of them asked if I would represent them again. Of course I said I would. As one or two made that decision, more followed.

After such a dramatic and public explosion, how did you handle reintegration into that world? Were you nervous?

I was . . . [long pause] . . . it’s funny, the year I got sober, the people who were in my life, some of them were still involved in publishing. Some of them were writers; some were editors and publishers. But they never mentioned to me what was going on in that world. They sort of protected me from the fact of it. And even knowing what was going on would have cost me something in my early sobriety. I couldn’t have beared it. When I did go back to work a year later, what mattered to me was different. What mattered to me were my friends, my sobriety, and the friends I’d gotten very close to in recovery. My expectations about going back to publishing were very low. I generally didn’t expect it would work, [since there was] a very good chance people would not trust me with their careers again. That said, when I walked through the doors of William Morris, I didn’t know people who worked at that agency. It was not a landscape of kindred spirits and friends. I felt very lucky to have a job, because at that point I had absolutely no money.

Yeah, you burned through it pretty quick in the end.

And I had great debts from rehab, from buying groceries on credit cards, from my legal bills. It was a terrible financial situation, but I still kind of had this sort of . . . I think when you go that deep into recovery for as long as I did, there’s a way in which you become comfortable with not knowing the outcome of situations. Just being sober and alive and healthy is the most important thing. Financial circumstances and status and your position in the professional landscape—all those things were generally peripheral to the gratitude I had for being sober, because it was so hard-won. And it was such a wonder. It was such a miracle.

That’s really interesting, too, because you don’t address the sobriety angle. The book is so centered on the high and the fall.

The point of the book for me was to show a frank glimpse of what happens as an addict. And also, to show the progression from my first drink at age 12 to trying to kill myself in a hotel room at age 34. That was my point in the book: to show how something can begin sort of innocently, and even be fun. Although for me, drinking was always a dark project. I was stealing alcohol and drinking it alone in my bedroom at age 12 and 13. And I ended up drinking alone and drugging alone. So it went full circle for me.

Your delusion was massive.

I believed, at the time that I was an active addict, that I could manage it. All through my 20s and 30s I tried to control what I drank, how much I used, what time I came home—and each time I would fail. And the point is that if anyone recognizes themselves at any point in that narrative—in their teens, their 20s, their 30s, or whatever—and they are trying to control their drinking and their drug use and they’re failing each time, it may suggest to them that it may go in the same direction it went for me. And if [I can help someone] avoid going in that direction, to the depth that I went, then the book is worth it to me.

There are some brutal scenes in the book. The paranoia of a drug addict—all of the men following you in their tacky suits. The “JC Penneys.”

Most of my perceptions were paranoid delusions. Whatever kernel of truth there was in there, that I was a drugged-out guy careening around the Newark airport post-9/11, it’s not that hard to imagine that there were a couple of people assigned to watch me. But a couple of people became a whole army of surveillance in my paranoid mind.

Your boyfriend tends to be an almost de facto hero in the book at times. And you put him through hell, going so far as to smoke crack and have sex with a prostitute right in front of him.

In that case, it was a situation where I don’t think he knew what to do. I think he was afraid that if he left, I would disappear and die. There’s no handbook on how to be the boyfriend or spouse of an addict or alcoholic, and he did the best he could. That memory, in fact, was lodged so deep that it didn’t surface until much later. It wasn’t until after rehab that I even remembered that. But it was an important memory because that moment had a lot of impact in it. It’s also important to remember where [drug addiction] takes you. It took me to a place where I could have sex with another man and smoke crack in front of my boyfriend. If that’s not an example of how one can abandon all sense of care and concern and love for another person, and serve as a warning to never do it again . . . There’s no [better example] of how disastrous my behavior became on drugs, and how I don’t want to return to it.

And your relationship did not survive that, correct?

We were apart for a year. I went to rehab and we didn’t see each other for a year and didn’t have any communication. It was the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my entire life. I thought I was going to die without him. He had been the only one who knew I was an addict, so subsequently I thought he was the only one who could ever love me because he knew the truth about me. And I believed that if anyone knew the truth about me that they would banish me, that I was genuinely unlovable. So I was very attached to him. And this cycle of my very dramatic behavior, and the shame of me being The Bad One and he being The Good One—that cycle played out so many times. It just sort of became the rhythm of my existence. And I’d never been on my own. It was very, very hard. But then, at the end of that year, he invited me out to dinner because he heard I was going back to work and I was healthy. And somewhere in the middle of the dinner he said, “Do we get to spend the rest of our lives together now?” Which of course was the only thing I wanted him to ask, and I said, “I hope so.”

What happened?

We got back together for a year, almost exactly. And what became clear was that relationship needed me to be an active addict in order for it to work—which is a heartbreaking thing to say, and it was a heartbreaking thing to realize. And we broke up. I was sober and I was different and the dynamic between us had changed and we weren’t meant to be together anymore. We’re now friends and we live three blocks from each other and we’re very supportive of each other. But it’s taken a long time for us to get there.

Are you busy being an agent, or is being an author taking up all your time now? I mean, you’ve been everywhere.

Well, I’m not going on tour. I’m staying very close to my job and my clients. Most of the press I’ve done is here in New York, or doing phone interviews.

I would think your agent would want you to go on tour. And your boss would be pissed off if you did go.

Well, my agent is my boss. She’s just a couple of doors down, so if it pissed her off, I’d definitely know. She’s a very clear, precise communicator. [Both laugh]

Who are you repping now that you’re really excited about? Anyone new you wanna turn us on to?

There’s a writer named Jenny Hollowell who has a book called Everything Lovely, Effortless, Safe that is just being published right now, which is brilliant. And two of my writers are in the “Twenty Under Forty” issue for The New Yorker—Rivka Galchen and Salvatore Scibona. And then one of my favorite books of all that I’ve ever represented is a first novel called Swimming by Nicola Keegan. It’s like The World According to Garp meets The Virgin Suicides, and it’s just one of the funniest, most heartbreaking and moving novels I’ve ever had the privilege of representing.

Thanks. Excellent reading suggestions for summer’s last gasp. Especially since this summer has sucked for movies. By the way, has your book been optioned?

No, not that I know of. [Laughs] It’s such a gloomy story I can’t imagine anyone making a movie of it.

How do you feel now?

I feel incredibly grateful for a job that I consider to be the greatest privilege. I feel grateful for the friends and family that I have in my life who I have now. I feel grateful to be in the world and to be alive.

Steven Foster also talks to Stephin Merritt in this issue of OutSmart magazine.