The Rest of the Story

Finding the truth behind the reversal of Texas’s sodomy law

by Brandon Wolf

On the evening of September 17, 1998, at approximately 10:30 p.m., a gay Houston man named Robert Eubanks used his cell phone to call the Harris County Sheriff’s Office and report that a black male was going crazy with a gun in unit 833 of the Colorado Club Apartments at 794 Normandy.

In a drunken state, Eubanks was livid about what he perceived to be flirtatious behavior between his on-again/off-again boyfriend Tyron Garner and John Lawrence, a mutual friend of theirs. Eubanks had only one thought on his mind: revenge.

Despite its maliciousness, that phone call put into motion a chain of events that led to a Supreme Court decision that many observers call “the gay community’s Brown v. Board of Education.” The high court’s decision would decriminalize homosexual conduct and forever alter the legal status of homosexuals in America.

Clarifying the Historical Record

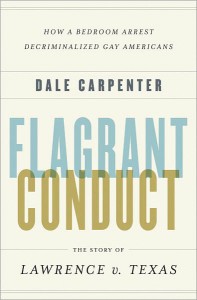

Lawrence v. Texas, the court case that emerged from the events of that September night, is the subject of a new book written by former Houstonian Dale Carpenter. As an attorney and activist, Carpenter was highly visible in Houston’s gay community in the 1990s.

One might assume that Carpenter’s book would be a tedious legal analysis of the landmark civil rights case. But Flagrant Conduct: The Story of Lawrence v. Texas is anything but tedious.

Carpenter takes the reader on a fascinating journey through the entire course of the case. The complexities of the U.S. justice system are explained in layman’s terms. The book also introduces us to previously unknown heroes of the case—people who were pivotal in moving it along. Without their involvement, the Lawrence v. Texas decision would not exist today.

Central to Carpenter’s story is the startling revelation that John Lawrence and Tyron Garner never had sexual relations on the evening of their arrest. That revelation might seem to gut the very core of the legal case that invalidated the nation’s sodomy laws. But as Carpenter shows us, Lawrence v. Texas is really about blatant homophobia that imploded in upon itself and caused the downfall of bad law and its even worse enforcement.

The Emergence of a Puzzle

Carpenter originally became involved in Lawrence v. Texas when he was asked to write an analysis of the Supreme Court decision for the Michigan Law Review. As he attempted to explain the case’s background, he

found that little information existed. There was never a trial, Lawrence and Garner had never been interviewed, and the legal team that handled the case was avoiding his questions.

Carpenter turned to his friend Ray Hill, Houston’s “godfather of gay activism.” Shortly into the interview, Carpenter asked about the men having sex. Hill responded, “Dale, you’re assuming they did have sex.” “Well, of course they had sex—that’s the basis of the case,” Carpenter countered. Hill answered, “You might want to look into that.”

Doing just that, Carpenter contacted local gay attorney Mitchell Katine, who had been active with the initial aspects of the case. On the issue of sexual activity between Lawrence and Garner, Katine would only offer that “we don’t talk about that aspect of the case.”

Carpenter then tracked down the two deputies who had filed the official arrest reports. Deputy Joseph Quinn told him that the men were caught in the act—in flagrante delicto—of anal sex.

But deputy William Lilly’s account differed radically. He remembered the men involved in oral sex. Realizing that it’s impossible to confuse anal sex and oral sex, Carpenter set out to unravel the puzzle surrounding this case.

What Really Happened That Night

In the mid-1970s, Beaumont transplant John Lawrence met Robert Eubanks in Houston. They were roommates for a brief period, but remained friends over the next decade.

Eubanks met Tyron Garner in 1990, and began a tempestuous, on-again/off-again relationship. Lawrence met Garner through Eubanks. Lawrence’s longtime companion José had moved to another city to take care of ill family members, so Lawrence was glad to fill the lonely gap by becoming part of a social threesome with Garner and Eubanks.

In September 1998, the Garner/Eubanks relationship was back on, and the two decided to move into an apartment together. Lawrence offered the men an old bed and other furniture he wanted to replace. So on September 17, the men moved the furniture and rewarded their efforts with dinner and drinks at Pappasito’s. Lawrence and Eubanks drank heavily at the restaurant, and continued drinking after returning to Lawrence’s apartment.

As the evening wore on, a drunken Eubanks became volatile and started accusing his friends of flirting with each other. A hostile argument ensued, and around 10:30 p.m. Eubanks said he was going downstairs to buy a soda. On his way out, he left the door slightly ajar.

Once downstairs, he placed his infamous cell phone call. Four Harris County deputies responded, with Deputy Quinn leading them up the stairs to the Lawrence apartment, their fingers “indexed” on the sides of their drawn pistols.

Meanwhile, Garner and Lawrence were in the living room area, waiting for a television news show to end. Garner was wearing only a pair of slacks, and Lawrence was in his underwear.

Quinn knocked on the door, causing it to open a bit. Then he swung it open, and the four officers burst in. They headed in different directions to search the apartment.

Lawrence, totally stunned, began cursing, but Garner remained passive. Eventually the officers announced that they were arresting Lawrence and Garner and taking them to jail. They gave the men no reason for the arrest.

Garner submitted, but Lawrence was outraged. The officers grabbed him and dragged him down the stairs. Refusing to stand up, Lawrence was bloodied and bruised as his legs bumped against the stairs.

The next day, the men were given orange jumpsuits and arraigned in a small courtroom at the jail. When they heard the charges filed against them—homosexual anal sex—they looked at each other incredulously.

They both pleaded “not guilty.” Booked and arraigned, they were now given enough clothes to cover themselves and were released. They hailed a cab to take them back to Lawrence’s apartment.

Bad Law and Even Worse Enforcement

To understand what happened to Lawrence and Garner, one only needs to recall the traditional treatment of homosexuals by law enforcement officers. For as far back as anyone can remember, police have charged gay men and lesbians with any charge they chose. The standard LGBT response was usually to plead guilty, pay a fine, and try to maintain as much secrecy as possible about the arrest.

Only the Harris County deputies know why they lied about what happened that night. Carpenter’s book lays out several factors that may explain their behavior: the Houston heat was oppressive; the deputies were on edge, anticipating a shoot-out; they had never been given sensitivity training for dealing with minority groups.

Additionally, the deputies harbored individual religious and cultural objections to homosexuality. They were angered by Lawrence’s cursing. They realized they were dealing with a gay “lovers triangle.” But the coup de grâce may have been Lawrence’s provocative bedroom art—posters of a naked James Dean with oversized genitals.

In any case, the deputies knew the accepted scenario for arresting gay men: “teach them a lesson” with a routine arrest and a trip to the jail, release them after they plead guilty, and they’re never heard from again. Little did they know that the reaction to this arrest would be nuclear legal blowback.

Paving the Way for History

Lawrence and Garner were given a date to appear before Justice of the Peace Mike Parrott on October 5, 1998. The jail faxed the charges to Parrott’s office.

It was pure serendipity that the fax was picked up by Nathan Broussard, a clerk in Parrott’s office and a closeted gay man whose partner was a Harris County deputy. Broussard couldn’t believe what he was reading, and discovered there was no computer code for the crime. He called his partner, who asked Broussard to fax the charges to his home.

Broussard and his partner liked to party on weekends at the now-defunct Pacific Street bar in Montrose. Their favorite bartender was Lane Lewis, and during the course of a conversation with him that weekend, they described the Lawrence and Garner incident.

Lewis, deeply involved in Houston’s gay activist community, was astounded by what he was hearing. He asked the men for a copy of the charges, and once he read them, he called Lawrence. Lawrence had no idea what a “gay activist” was, but agreed to meet with Lewis, who already suspected that the case was pure activist gold.

The Texas sodomy law was rarely enforced, and then only when sex was occurring in a public place. Attempts to challenge it were rejected by the civil courts. What activists needed was an arrest in the privacy of a home.

Lewis explained this to Lawrence, and asked him to become part of a legal challenge. At first, Lawrence declined. Lewis then changed the course of gay history by launching into an emotional soliloquy that invoked the names of pioneer gay activists from Harry Hay to Harvey Milk.

Lawrence was deeply touched, and told Lewis he would cooperate. Lewis then contacted Ray Hill, who referred him to Mitchell Katine.

Bringing in the Big Guns

Katine then contacted Lambda Legal, a national organization that had been involved for the past 25 years in legal challenges on behalf of the nation’s gay community. Lambda advised the men to plead “no contest” and pay the fine.

From the very beginning, everyone involved agreed that Garner and Lawrence had to be completely shielded from the media. Lambda wanted no jury trial, no officers on the witness stand, and no words coming from the accused men. “We never lied,” says Katine. “We just didn’t dispute the validity of the charges.”

Lawrence found the situation to be a special sacrifice, because he had always been faithful to his partner, José. But for the sake of the greater good, he consented to maintain the illusion that he and Garner had been sexually intimate.

Over the next four years, the case made its way through the Texas criminal court system. Finally, in late 2002, the case had reached the point where a writ of certiorari could be submitted to the Supreme Court. Only one percent of the writs submitted to the high court are accepted.

It was a time for celebration when the Supreme Court granted the request on December 2, 2002, and scheduled arguments for March 26, 2003. Lambda was especially pleased that the justices asked that the 1985 case of Hardwick v. Bowers be addressed in the required pre-hearing briefs. In the Hardwick case, the Supreme Court declared that there was no constitutional right to engage in homosexual conduct.

Carefully Crafting a Strategy

Lambda prepared a brilliant case against the Texas sodomy law. They explained why the law, which applied to homosexuals but not heterosexuals, violated the 14th Amendment to the United States Constitution’s guarantee of equal protection under the law.

Then they outlined why the prohibition against sexual intimacy in one’s home violates a citizen’s liberty and privacy, which is protected by the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. In conclusion, they presented their justification for overruling Bowers v. Hardwick.

Lambda also submitted a carefully chosen group of amicus briefs, in which supportive parties addressed the issue of homosexual rights from every possible angle. American attitudes about homosexuality had changed dramatically in the intervening 17 years since Hardwick. Lambda emphasized that by ruling in their favor, the court would not be “leading,” but rather just “catching up.”

Attorney Paul Smith was chosen to argue the case. He was unknown to the gay community, but was a seasoned lawyer who had argued several cases before the Supreme Court. He knew how to play the game.

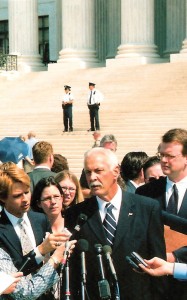

On the opposing side, Harris County District Attorney Chuck Rosenthal assigned himself to argue the case. He was clearly out of his league, and the Texas briefs were similarly uninspiring.

The justices spent one hour listening to the arguments on March 26, 2003, with the time divided equally between the Lawrence and Texas teams. Smith was stellar; Rosenthal was so hopeless that eventually the conservative justices gave up trying to rescue him.

During the arguments, all eyes were on Justices O’Connor and Kennedy, the “swing” voters in the decision. Neither justice offered any clues as to their feelings.

After an agonizing three-month wait, the court chose the last day of their term—June 26, 2003—to release their opinion. At 10 a.m., the justices took their places in the courtroom. At 10:08, Chief Justice Rehnquist announced that the majority opinion in the Lawrence v. Texas case would be read by Justice Kennedy.

Eighty percent of the people in the courtroom that day were gay activists, and they hung on every word of Kennedy’s reading. He began his nine-minute reading by reviewing the 400-year history of sodomy laws. By 10:10, Kennedy began to address Bowers v. Hardwick. Two minutes later, he took a deep breath and said that Bowers “failed to appreciate the extent of the liberty at stake.”

Throughout the audience, eyes began to glisten. Many tried in vain to hold back their emotions. Tears began to stream uncontrollably down their faces.

By the end of the reading, activists’ minds were reeling. The Supreme Court had decided in favor of Lawrence. They announced that their Bowers v. Hardwick ruling was now overturned. But the real stunner was the court’s unprecedented apology for that 1985 ruling. The timing of the decision was unbelievable—just two days before the nation’s annual Gay Pride celebration of the 1969 Stonewall Riots anniversary.

Epilogue

The Supreme Court based its historic decision on the Constitution’s Due Process Clause, which protects citizens from state laws that limit fundamental freedoms. The effect of that rationale was to strike down the remaining sodomy laws in 14 states on June 26, 2003.

Even though those 14 states rarely enforced their sodomy laws in a literal sense, their mere existence psychologically enforced the absurd notion that homosexuals are de facto criminals—and thus unfit for the privileges and responsibilities of full citizenship.

Tyron Garner died of pneumonia in 2005. John Lawrence suffered a stroke in early 2011, and died a few months later. However, before his passing, he invited Dale Carpenter back to Houston for a final interview. This time Lawrence spoke freely, and said he wanted history to get his story right.

Lawrence also gave Carpenter the infamous James Dean posters that may have provoked the Harris County deputies to arrest Lawrence and Garner in 1998. But Carpenter doesn’t claim ownership. “They belong to the nation’s gay community,” he says.

Besides leaving LGBT Americans with a greater measure of equality and a place at the table, John Lawrence left his posters as a final gift to us and to future generations—tangible reminders of a hot September night in Houston that forever changed our lives.

Brandon Wolf is a frequent contributor to OutSmart magazine.