Painful Tales

Gay American black men tell their stories

by Kit van Cleave

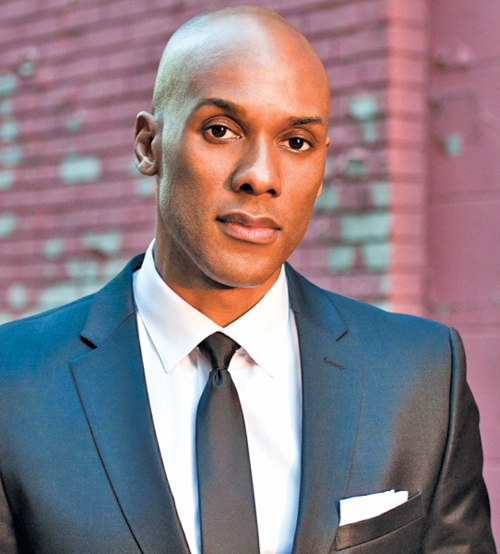

Keith Boykin has had a lot of experience with the despair of being a gay American black man who was bullied and humiliated in childhood for not living up to an über-masculine image.

In the introduction to his new anthology For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Still Not Enough, Boykin recalls trying to estimate the number of U.S. gay men who have recently committed suicide, including friends. These personal tragedies moved him to request submissions for a new anthology about black men who suffered through their childhoods and coming-out periods. The resulting book is a remarkable group of essays from successful men like himself who have distinguished academic and professional backgrounds.

Their stories, however, are marked with pain. Most seemed to know very early—at five or six years of age—that they were gay, and most of them also had childhood sexual experiences. Their communities and relatives forced them into the closet with name-calling or threats.

Only a few of these writers were effeminate; several were pro football or basketball players, and others served in Iraq. While they all finally found their way to sanity and inner peace, their struggles cost them their adolescence, relatives, friends, jobs, and sometimes even their parents.

Daren J. Fleming, in “The Night Diana Died,” remembered when he was part of a group of four out black men attending Millikin University in central Illinois. He and his “boys” went shopping before a theater party, and some of them were “flaunting” on the streets when several white men in a pickup tried to run over them. Later, at the party, a girl came up to Daren and told him the “townies” had infiltrated the party and were looking for them to beat them. Other students helped them to narrowly escape the party. It was a bone-chilling experience followed by a rash of anti-black and homophobic incidents in the small college town.

In “Just the Two of Us,” Curtis Pate III recalled when he took his lover, Carwyn, home to meet his parents as he was coming out. His parents had always been supportive and loving. However, when the introduction came, his father stood and said, “I don’t want to hear about these sick feelings you have. I want you and that thing out of my house, now.” For the next ten years, he never spoke to his folks about his life. When he finished Rutgers University, became financially successful, and bought a home—with Carwyn—his family finally accepted them both.

In “Just the Two of Us,” Curtis Pate III recalled when he took his lover, Carwyn, home to meet his parents as he was coming out. His parents had always been supportive and loving. However, when the introduction came, his father stood and said, “I don’t want to hear about these sick feelings you have. I want you and that thing out of my house, now.” For the next ten years, he never spoke to his folks about his life. When he finished Rutgers University, became financially successful, and bought a home—with Carwyn—his family finally accepted them both.

Highlighting the close relationship between the black community and Protestant churches, Boykin notes that several of these writers were lay ministers as teens, taught Bible study classes, and then were excluded from leadership positions when their secret was revealed. Some of the writers are quite hostile about how pastors—many of whom are gay—thunder from the pulpit about the damnation and hellfire brought on by homosexuality. Even today, the hypocrisy is staggering; black churches accept gay people as long as they never speak about sexual issues.

A particularly touching story was filed by José David Sierra, better known as the drag performer Jessica Wild. Born in Puerto Rico, he was always more feminine than masculine, so his schoolmates, aunts, and cousins taunted him early on with a variety of insulting names—pato, maricon, loca, nena. As a result, he spent much time alone, writing, dancing, drawing, and creating music.

When Sierra was sixteen, his mother allowed him to start dance classes, and he immediately started planning a career in show business. As he started going to gay clubs and saw drag queens for the first time, he decided he should do drag because his purpose in life was to entertain. His friends helped him, and soon he was a popular entertainer all over the country.

When RuPaul had a concert in Puerto Rico, the producer asked Jessica Wild to be in the opening of the show. Due to his subsequent TV appearances, Sierra’s parents soon discovered not only that he was gay, but a drag performer. Their reaction: “El es mi hijo. No importa lo que haga lo voy a reconocer.” (“He’s my son. I’m going to know my son no matter what.”)

After Sierra first saw RuPaul’s Drag Race, he auditioned for the second season and was chosen. He flew to Los Angeles for the international hit show, and his career took off. Today he says, “It’s just about doing what I love and making your dreams come true.”

The title of Boykin’s anthology comes, of course, from Ntozake Shange’s play, first presented in New York, about a group of women who suffer indignities and tragedies, yet continue to thrive. For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow is Enuf (1974) was produced in 2010 as a film starring Janet Jackson, Whoopi Goldberg, Anika Noni Rose, and other major actresses of color.

Boykin has certainly reclaimed his life, having attended Harvard Law School with President Obama and served as a special assistant to President Clinton. He is currently serving as a political commentator for CNN, MSNBC, and CNBC.

Thoroughly recommended.

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.

For Colored Boys Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Still Not Enough

Edited by Keith Boykin

2013 • Magnus Books (magnusbooks.com)

280 pages • $15.95 • paperback