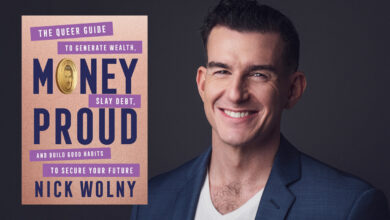

‘The Up Stairs Lounge Arson’ and ‘Let the Faggots Burn’

by Clayton Delery-Edwards

2014 • McFarland (mcfarlandbooks.com)

216 pages • $40 • Paperback

Let the Faggots Burn: The UpStairs Lounge Fire

by Johnny Townsend

2011 • Booklocker.com, Inc. (booklocker.com)

342 pages • $17.95 • Paperback

by Kit van Cleave

Sometimes the sweetness and generosity of the gay community really sets a moral standard. When Johnny Townsend started writing his book Let the Faggots Burn in l989, he was an English graduate student with no training in history. But he was driven to tell a story.

On June 24, 1973, the deadliest fire in New Orleans history occurred. It was inside the Up Stairs Lounge, a gay bar at 141 Chartres Street, off the main tourist drag in the French Quarter. When the 16-minute blaze was put out, 29 people were dead, their bodies littering the streets outside, inside the bar, and in various escape avenues. Three more later died of their injuries.

“I simply wanted the story to be recorded and told before too many people were lost to AIDS and age,” Townsend noted in his foreword. He had no interest in making money from the tragedy; he had met the friends and families of people who died in the bar. His manuscript had no footnotes for interviews, media reports, or police investigations. He simply wrote from his heart about people who had loved, lived, struggled, and celebrated at the bar.

Townsend left his manuscript for years at the Historic New Orleans Collection in the French Quarter, and at the National Gay and Lesbian Archive in L.A. He merely hoped his draft would be available to anyone doing further research on the fire. Now a new book has come out—The Up Stairs Lounge Arson by Clayton Delery-Edwards. It’s a much more detailed account of the before-and-after of the deadly attack on patrons of the Up Stairs, and it’s an essential read, especially for young gay people who have no idea how deep the homophobia of the late 20th century ran.

From the several spellings of the lounge’s name (was it Up Stairs or UpStairs?) to forensic reports, Delery-Edwards’s book provides facts unavailable in the late 1980s, when Townsend began his research and interviews about the arson.

In 1970, Phil Esteve inherited $15,000 from his mother. At 39, he wanted to open his own business. Having a drink at a gay bar called The Cavern, he started discussing with a bartender what kind of business he’d like to have. The casual meeting was prophetic, as the bartender, Buddy Rasmussen, told him if he was interested in opening another bar, he’d have to have a bartender he could trust.

Esteve hired Rasmussen on the spot, not knowing that Buddy would be the hero of the fire at the Up Stairs two years later.

Together, they found a space on the second floor overlooking Chartres Street. The only entrance was an easily overlooked door on Iberville. The front room was filled with utility meters and plumbing, so Steve and Buddy carpeted the stairs and draped the walls and pipes with yards of fabric. While seven windows looked out into the streets, when the lower sash was raised, a customer could easily fall out onto the concrete below. A previous tenant had put horizontal bars across these windows for safety, and many of the sash cords were broken, making the windows difficult to open anyway.

Another room had an additional three windows, painted black on the inside. The two young entrepreneurs walled over two of the windows behind the bar and three of the windows in the middle room. They painted, and carpeted, and laminated the bar top in a color scheme of pink and orange.

“Though descriptions of red carpet, red drapes, and flocked wallpaper strike people today as garish, The Up Stairs, in its day, had a reputation for ‘discreet elegance,’” writes Delery-Edwards. Phil Esteve also set some boundaries: he did not permit hustling, drugs, tearoom sex, and discouraged hustlers from even coming to buy drinks. “Phil and Buddy were so eager to maintain a clean atmosphere in the Up Stairs that they reportedly issued open invitations to the police vice squad to drop in at any time,” Delery-Edwards notes.

Indeed, in both books about the arson, the lounge is described as a favorite drop-in spot, with many regulars who all got to know each other very well. The space was rather small, and since good behavior was required, both gays and straights were comfortable as patrons of the bar.

One night, Buddy Rasmussen had to evict a young customer who had been bothering others in the men’s room. As everyone knew, Phil and Buddy didn’t allow such antics; the young man, Rodger Nunez, swore he’d return. Soon after, a woman on the street outside noticed a small fire burning at the bottom of the lounge’s stairs to the second floor. In a few seconds, it started climbing up, and within a minute or two, flames burst into the main rooms.

Rasmussen immediately started herding customers toward exits at the back of the bar. Some customers rushed for the windows but were too large to slip through the protective bars. Many simply panicked, and as the fire licked toward the low ceiling, black smoke roiled through the space, blinding people to any other exits. Though the New Orleans Fire Department was on the scene in about seven minutes, by that time most inside the Up Stairs were already dead or dying.

The head of the city’s Metropolitan Community Church, Bill Larson, vainly tried to get out one of the front windows, but it was too late. Those standing outside the scene saw his body partway out of the window.

But the worst was about to happen. Local Catholic archbishop Philip Hannen refused to allow any Catholic funerals or burials for the victims. He did not go to the hospital to visit the victims or their families; he did not call for prayers or for Catholics to donate blood for survivors. The Episcopal bishop of Louisiana, Iverson Noland, refused to allow any funerals in any Episcopal church. Many victims were outed to their families by the media covering the tragedy.

As to who said, upon arriving at the scene, “Let the faggots burn,” it was reported by gay people standing outside the bar and watching attempts to extinguish the fire. The remark was attributed to either a fireman or a policeman, depending on who was repeating it.

However, the “jokes” circulating in New Orleans after the arson reflect the thinking of the time. Townsend writes, “Gays who heard comments on the street or at work like ‘I hope they burned their dresses off’ and ‘It was only faggots. Why worry?’ had to pretend not to take offense,” he wrote.

“So they’d hear jokes such as, ‘What major tragedy happened in New Orleans on June 24? That only 30 faggots died and no more!’ or the joke that began ‘Did you hear the one about the flaming queens?’ and try desperately to keep the rage inside,” Townsend recalls.

Delery-Edwards notes Townsend’s references about these “jokes” and includes a children’s cereal in the remark that “the fire had turned a bunch of fairies into Crispy Critters.” A New Orleans radio host suggested on-air he’d recommend disposing of 30 gay men by “burying them in fruit jars.”

The principal difference between these two books is Townsend’s heart-rending descriptions of the victims; they seem to come alive once more. Delery-Edwards provides a factual update, including that Nunez not only confessed having set the fire to friends, but committed suicide in 1974.

Today, a metal plaque in the sidewalk marks the date and victims of the arson. That memorial and these books will forever be the most accessible record of the events. Townsend gives touching accounts of the lives lost in the fire; Delery-Edwards provides the framework of their deaths.

Editor’s note: As Townsend uses “UpStairs” and Delery-Edwards uses “Up Stairs” for the name of the bar, both were used here in quotations about the books.

Kit van Cleave is a freelance writer living in Montrose. She has published in local, national, and international media.