BOOKS: ‘Buzz’ Provides A Stimulating History of Sex Toys

By Terri Schlichenmeyer

Double-A. It has many uses, that little word-dash-letter. It’s good for future baseball players. Good for a pre-teen girl. Great, if you’re a student trying to bring those grades up. And, as you’ll see in Buzz: A Stimulating History of the Sex Toy by Hallie Lieberman, if you’re an adult, Double-A is something you never want to run out of.

A dozen years ago, to make a little money, Hallie Lieberman found an unusual job: she was a home-party sex-toy salesperson in a state where the selling of sex toys was illegal. Ever afraid of being arrested, she stuck to a script that the company gave her. It was stilted and full of euphemisms, and the job was demeaning and embarrassing. She felt like she “wasn’t actually teaching people anything.”

From her doctoral studies, Lieberman learned that “sex toys were ancient.” Some 30 millennia ago, ancient Germans carved phallic objects, though some historians argue that stimulation might not have been their intention. At any rate, the practice of using artificial devices for sexual pleasure spread across Europe and into Asia. Soon after the Middle Ages, mentions of sex toys began showing up in literature.

by Hallie Lieberman

2017

Pegasus Books (pegasusbooks.com)

359 pages

$26.95/$35.95 Canada

Beginning in Victorian times (and closer to home), rectal dilators and vibrators were made in the U.S. and approved by doctors to be sold as “medical devices.” The dilators were made by “respected rubber companies,” while the vibrators could be discreetly purchased in department stores for decades. Until it was outlawed, you could even have the devices mailed to your home. To circumvent the laws meant to keep sex toys out of the hands of everyday citizens, vibrators, dildos, and dilators had to be sold as “novelties.”

In 1965, an engineer (who was also a ventriloquist!) started manufacturing sex toys. In the early 1970s, a paraplegic welder began making them for women and advising the disabled on their use. Other vendors joined the revolution until, in 1972, sex toys gained respectability inside a small waterbed-store-turned-sex-shop run by two gay men (who welcomed hetero people).

Of course, there’s so much more to this story, but here’s one interesting thing about Buzz: while you might think the book would be titillating (and heavy on nudge-nudge-wink-wink passages), that’s not the case. Author Hallie Lieberman doesn’t do that to her readers. Instead, what you get is exactly what its subtitle promises: a history of sex toys throughout history, and their use by straight people, the disabled, the LGBT community, and feminists.

Through the narrative, you’ll see how advocates tied sex toys to equality and self-confidence, and how the struggle to make the devices acceptable unfolded—and is still not over (including a surprise-not-surprise toward the end). That’s serious stuff, and Lieberman offers it in a well-rounded way, though not without lightheartedness when appropriate.

Buzz is a book meant to inform rather than to shock, and that is enjoyably accomplished. The prurient, the curious, and the fans of pop-culture will love Buzz—no batteries required.

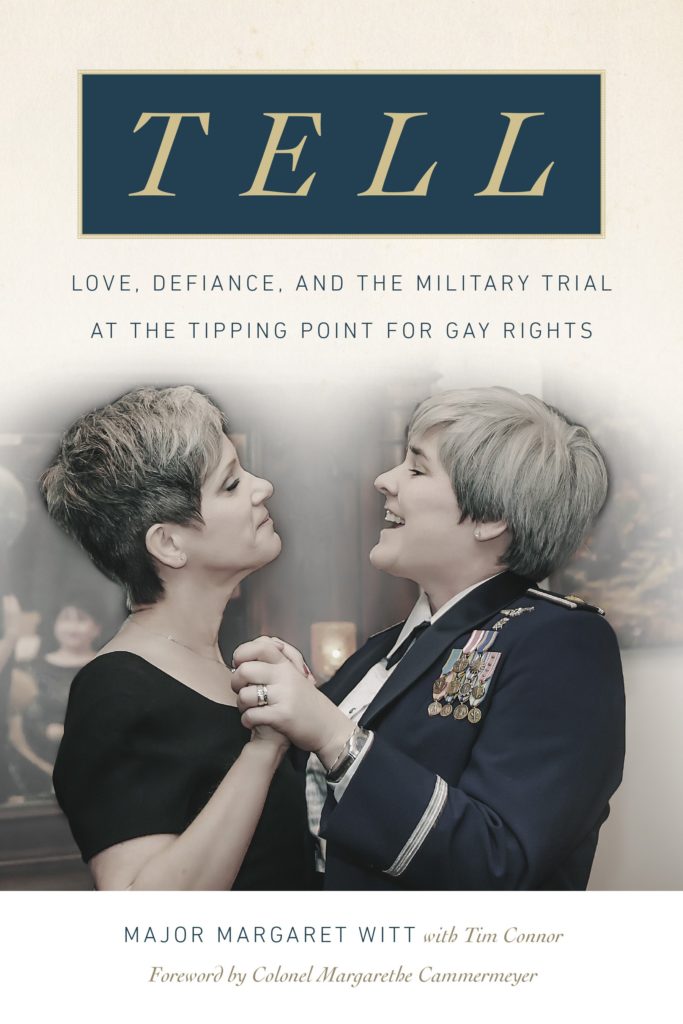

‘Tell: Love, Defiance, and the Military Trial at the Tipping Point for Gay Rights’

Major Margaret Witt with Tim Connor, foreword by Colonel Magarethe Cammermeyer

For those who love her, Margie Witt was always known as a take-charge, caring person. A tomboy growing up, she befriended the friendless, got along with everyone, and was a super-responsible leader. It was, therefore, a natural fit when, in 1987, Witt decided to join the Air Force, even though she was gay.

But of course, nobody was supposed to know that. As an elite member of the military, Witt fully understood that in 1987, just being gay meant a military discharge. Even Witt’s girlfriend was mum, but there was trouble on that front: Tiffany desperately wanted a baby and was pressing, but Witt was uninterested in parenthood.

With a pregnancy-or-else deadline looming, Witt kept busy, was sent to the Middle East, and received commendations for saving a life there. But as her relationship crumbled, she needed a confidante. Witt turned to a female colleague who soon became more than just a friend with a sympathetic ear.

In the ensuing “very, very ugly” divorce, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was no longer possible.

There’s much more to the story—sometimes too much. But stick around: things move faster in the aftermath of Witt’s exposure and the fight for gay rights in the military. That’s what makes Tell highly readable and deeply personal.

FB Comments