A Guide to Greatness

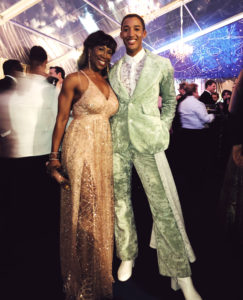

Houston Ballet’s Lauren Anderson inspired soloist Harper Watters’ success.

Harper Watters, the Houston Ballet’s dynamic young soloist, remembers the moment he first saw Lauren Anderson. “I was a teenager at the Houston Ballet Academy for a summer intensive training session. I was standing in the hallway with some friends, and I saw this woman coming toward me. It was like the sea was parting for her. She was just magnificent; she had such a presence. I asked my friends who she was, and they told me she was Lauren Anderson, the Houston Ballet’s first Black principal dancer.”

Soon after that, Watters was offered a place in the Houston Ballet II, the company’s pre-professional training arm. Watters was 16 years old, already openly gay, and still in high school.

“Lauren walked up to me a little while after that and said, ‘You got into Houston Ballet II? You’re going to take it, aren’t you? You have to take it.’ I told her I wanted to, but my parents were a little nervous about me moving to Texas.

“She talked to them. She told me I had to accept the offer and come to Houston. My parents thought maybe I should wait a year, but Lauren told them, ‘No. It has to be this year. His time is now. The opportunity is here right now. Next year, there might not be a slot for him. There might not be another offer.’ And she was right. Anything can happen in a year. So they let me come. It changed my life.”

Anderson remembers that conversation well. She had seen Watters in a dance class and was impressed with how regal he was, and how well he moved. She was very enthusiastic about such a talented young man joining the company.

“I told his parents that he’d be nurtured and understood—both as a dancer and as a person of color—because they had been through it with me,” Anderson recalls.

“And I told him, ‘Once you’re here, you’re mine. I will take care of you.’ And he’s done wonderfully here.”

That was 2009. Watters performed with Houston Ballet II until 2011, when he won the Contemporary Dance Prize (and sixth place overall) at the Prix de Lausanne dance competition. He joined the Houston Ballet that same year as an apprentice and moved up the ranks. In 2017, he was promoted to soloist.

Watters explains that Anderson has been more than a mentor to him.

“She’s actually my fairy godmother,” he says, laughing. “She’s always been there for me. Early on, she would come up to me and tell me that I had to work harder—to really dedicate myself to my training. ‘We need a black Prince!’ she’d tell me.”

Anderson was referring to the coveted Prince role in The Nutcracker, a milestone for male dancers.

“I did tell him that,” she says. “I wanted him to know that he was prince material, that he could get there if he worked hard. And he did.” Watters most recently performed as the Prince in the Houston Ballet’s 2019 production of The Nutcracker.

Watters adds, “I knew I wasn’t going to get the Prince role just because I was African-American. I had to be a strong dancer. My talent was going to get me the role, not the color of my skin.”

Anderson agrees. “Houston Ballet doesn’t harp on the color thing at all. It never has. You do find that [color is an issue] when you go to other places, or when other choreographers come to set a work on the company here. But it was never a factor here. Since the beginning, Houston Ballet just wanted the best dancer for the role. Period.

“I was Alice in Alice in Wonderland in 1979 at the Houston [Ballet] Academy. Alice is the whitest of the white characters, so obviously [skin color] isn’t the focus of the Houston Ballet. Cinderella and Sleeping Beauty—Disney made them white, but Houston Ballet didn’t because I danced both roles.”

Other American ballet companies have lagged far behind Houston Ballet when it comes to having African-American dancers in major roles. Misty Copeland became the first African-American principal dancer for American Ballet Theatre in 2015; Lauren Anderson was made principal for Houston Ballet in 1990, a full quarter-century before.

Charlotte Nebres became the first African-American Marie in New York City Ballet’s The Nutcracker this past December. Cleopatra Williams had danced that role starting in 2001 for Houston Ballet.

“Houston Ballet hired its first Black dancer, Adrian Vincent James, in 1976. And they didn’t do it because he was Black; they did it because he was a great dancer,” says Anderson.

Still, Anderson notes that diversity is important, especially for young audiences. “Kids need to see us onstage,” says Anderson.

Both Watters and Anderson were children when they first saw African-American ballet dancers onstage. And for both of these star dancers, it was a defining moment. The Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater had visited the University of New Hampshire, where Watters’ father was a professor, and the family attended the performance.

“As a little kid I was always moving, always busy,” Watters explains. “But my parents said that when I was watching Alvin Ailey Dance Theater onstage, I was absolutely still, like a statue. I was just mesmerized.”

The same was true for Anderson, who was nine years old when she first saw the Dance Theatre of Harlem. At that performance, she realized she had never seen an African-American ballet dancer. Anderson was already training at the Houston Ballet Academy at that point, but it was still a shock.

“It had never occurred to me that I hadn’t seen a Black ballet dancer—until I saw a Black ballet dancer,” she says.

Watters, now 28, says that after almost ten years in the company, he continues to seek out Anderson for nurturing and career guidance. “I drop by her office every few days. Sometimes just for a hug, even. She doesn’t know it, but she has meant so much to me. Being a dancer is difficult. You’re always competing for roles. You’re worried about injuries. Trying to do your best at every performance. It’s hard. But having Lauren in my corner is amazing. I know I can do it, because she thinks I can. She tells me I can.

“She knows how hard it is, because she’s done it. And if, knowing how hard it is, she thinks I can do it, then it must be true.”

Watters has a huge social-media following, and he knows that he’s very visible. As a gay man, as an African-American, and as a ballet dancer, he’s a role model to young people.

“Lauren was a role model for me, not just because she was African-American but because she was fierce, she was confident. I hope that I can be an example for young people.

“Whatever it is about me that they identify with—because I’m gay, because I’m a dancer, because I’m African-American, whatever—I hope they can look at me and say, ‘I can be successful like he’s been successful.’ And the truth is, they can.

“Lauren was an example for me on so many levels. I just love her.”

This article appears in the February 2020 edition of OutSmart magazine.