Forensic Artist

Nonbinary Houstonian Ángel Lartigue heads to Australia to research and create.

By the time you read the following description of all the disciplines that Houston-born-and-raised nonbinary artist Ángel Lartigue has explored, they will have decamped for several months to the unlikely destination of Perth, on the Western coast of Australia. Lartigue has been invited to participate in the prestigious art and biological science research center SymbioticA, an artistic laboratory dedicated to research, learning, critique, and hands-on engagement with the life sciences.

As Lartigue’s nontraditional practice has grown, they are comfortably referred to as both an artist and a scientific researcher in forensics. As a mystic and rationalist, performer and object maker, entertainer and shaman, butch and femme, Lartigue cuts a compelling figure in culture, science, and nightlife. Encountering them is sure to make an impression, for better or worse. Even if you are encountering the deathly, musky smells of decomposition in a dark nightclub, I urge you to push past your queasy feelings and engage deeply. It’s worth the effort.

My first encounter with Lartigue was in 2017 as I walked into the Box 13 artist space and saw Lartigue chained to an altar with rosary beads. Since I had arrived at the very start of the performance-art event, I would be Lartigue’s first experimental subject for Sub Scientist Booth.

According to the artist’s description, “[the booth’s] conceptual basis consists of a scientist restrained (with a rosary leash, fence chain, clay shackles, etc.) while they extract participants’ DNA substance using only household items such as salt and water to mouth-swish cheek cells. The process takes less than five minutes to execute, all while the participant observes. The participant takes home a raw sample of extracted DNA substance from the scientist in exchange for their own DNA. On occasion, blood is also given as an exchange.”

During my Sub Scientist Booth encounter, I was instructed to sit on the floor next to the artist, swirl a fluid around my mouth, and spit it back out. Lartigue then produced a twisted strand of my genetic material along with a specimen of Lartigue’s. Lartigue’s outfit, with its S and M overtones, brought up some darker queer erotics (if, in your sir/slave relationship, how Dom can you really be if you aren’t controlling your Sub at a cellular level, twisting their DNA to your sadistic whims?). The BDSM dynamics under the surface of scientific research has been analyzed by feminist theoreticians of science like Evelyn Fox Keller and Donna Harraway. I was reminded of the opening passage of Harraway’s The Companion Species Manifesto in which she imagines her DNA commingling with her dog’s after a particularly wet canine kiss. But Lartigue’s performance brought that theoretical idea memorably home.

As part of the first generation of LGBTQ folks who no longer need to think of all body fluids of lovers as potentially toxic, and invisible microbes as mortal enemies, Lartigue nonetheless tends to focus on end-of-life events. Lartigue describes being nonbinary as the rolling dice of their art, never knowing how that will direct their investigations. It creates a unique perspective: bodies and biology as raw material for art, politics, and self-invention.

In Lartigue’s nightclub persona (or personas), they collaborated with the larger-than-life personalities Farrah Fang and Mystic Stylez, who mysteriously go by another name as an art gallerist and curator duo. Their events happen too late at night for me, and remain under the radar of the larger art worlds, so they are not reviewed in the Chronicle or on Glasstire.

These queer nights had colorful names like “Trust Me Daddy,” and featured performers like the internationally celebrated House of Kenzo and the composer Rabit. They have become the stuff of legend in the polymorphously perverse, radically inclusive, and diverse queer underground space that Houston is known for allowing to flourish.

As a first-generation American whose parents arrived from Mexico in the ’80s, Lartigue has always slipped between cultures, political regimes, and religions. Being more interested in linguistics, Lartigue never pursued an art degree. Their focus turned to the way the human body is only comprehensible when located on and cleaving to the rich soil of the earth itself, just as Whitman-esque poetics turns into the muck of the soil before transforming yet again into leaves of grass.

Dead bodies lying exposed on the ground are commonplace in certain border areas of Texas. The New York Times reported that over 300 dead are found every year on the ranches along the border with Mexico, with Brooks County being infamous for the toll its harsh terrain takes on underprepared migrants hoping to find a better future. Students at UT-Austin try to exhume bodies buried in mass graves, but most are never identified and families are left to wonder.

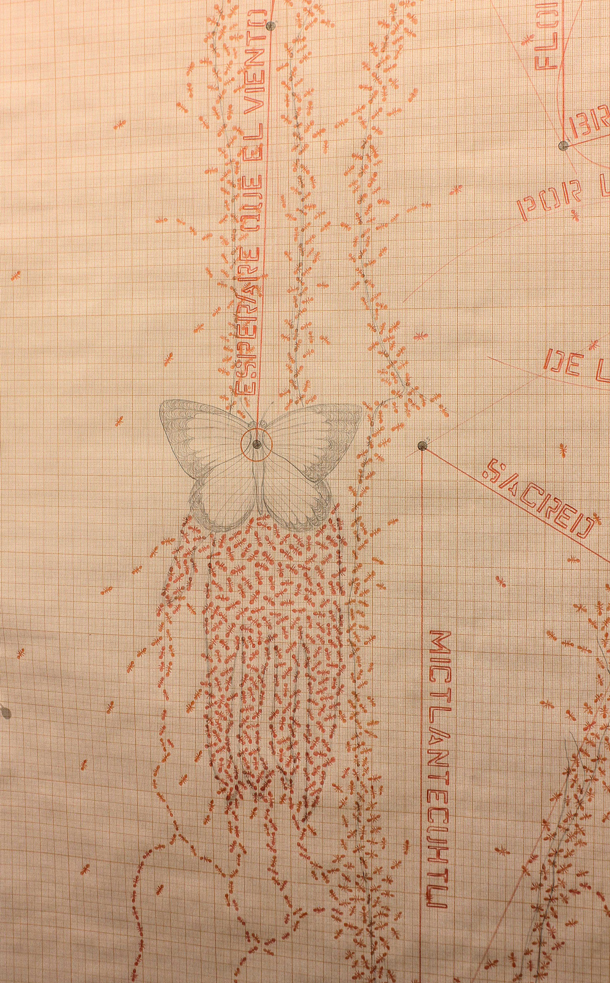

In 2015 and 2016, Lartigue did a series of performance-based photographs called Muerte, in which the artist’s body is seen twice in the same frame—first naked and dead, then alive and dressed. Although many photos depict urban settings, some show remote natural situations that bring to the fore the idea of a body turning back into soil and landscape.

Lartigue became curious about what happens when a dead body is left outside in the harsh Texas weather. This new area of artistic research was fueled both by his artistic interests in the earth and also his family history that includes a brother of his grandfather who disappeared and was never found. “A lot of people think I am detached after seeing so many bodies, but I am not at all. I have a very personal connection to the refugees, as well as a political identification.”

Lartigue enrolled in a forensics program to learn how to get maximum information while recovering human remains, ideally to give closure to children and families back in Central America who wonder if the “I arrived and have a job” call will ever come.

The massive, ongoing humanitarian tragedy has captured Lartigue’s imagination, and the photos he made while learning to study corpses are memorable indeed. As the refugee crisis will only intensify as climate change and economic inequalities worsen, Lartigue’s work in particularly vital.

Back in Australia, Perth should feel like home to Texas-raised Lartigue, as the city is known for a cowboy culture that coexists with Balinese dance rituals and other Southeast Asian cultures. Perth is also a great distance from the hip international center of Sydney, just as Houston is far removed from the trend-setting U.S. coastal meccas.

SymbioticA has hosted the most celebrated biology-based artists working today, including Stellarc and Orlan. Yet, the question of what it means to work in Australia in 2020 looms large. Today’s Australian bushfires are a symbol of the worsening, self-inflicted hell we have created by ignoring the climate-scientists’ warnings. Hopefully, having Lartigue work with these artists and scientists their will create a dialogue of value—maybe not enough to save the planet, but enough to help us see the meaning and beauty of our bodies’ inevitable return to the earth.

For more information, visit Angel-Lartigue.com.

This article appears in the February 2020 edition of OutSmart magazine.