The Aggie and the Ecstasy

An interview with filmmaker Catherine Gund.

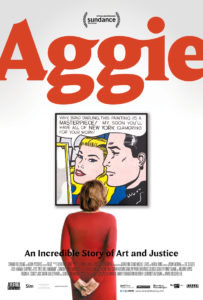

Lesbian documentary filmmaker Catherine Gund has an exceptional eye for subject matter when it comes to her movie projects. Of course, it helped that she was already familiar with gay performance artist Ron Athey, the late lesbian Mexican singer Chavela Vargas, and lesbian choreographer Elizabeth Streb. And she’s especially well acquainted with the subject of her new doc Aggie (Strand Releasing/Aubin Pictures), which is about art collector and philanthropist Agnes Gund, who is also Catherine’s mother.

Agnes’ name may be familiar to some readers from her tenure as president of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Others may recall her incredible act of generosity when, after selling a piece of art from her private collection in 2017—Roy Lichtenstein’s Masterpiece—for an estimated $165 million dollars, she donated $100 million dollars from the sale to establish Art for Justice, a grant-making organization “focused on safely reducing the prison population, promoting justice reinvestment, and creating art that changes the narrative around mass incarceration.”

Can you even imagine a subject more worthy of a documentary? Of course, that was director Catherine’s greatest challenge, because her mother prefers to stay out of the limelight. Nevertheless, you’ll be glad that Catherine prevailed, because Aggie is a truly delightful and eye-opening work of art.

Catherine Gund was kind enough to chat with OutSmart before the film’s release.

Gregg Shapiro: Catherine, you have a history of making docs about undeniably fascinating people, including Chavela Vargas, Ron Athey, and Elizabeth Streb. What is involved in your decision-making process when it comes to the subjects for your films?

Catherine Gund: I love this question about how to identify fascinating people, because I never set out to profile someone or make a movie about someone. It’s always been somebody who’s already in my life, and then it sort of develops into this story that I feel is always much bigger than that person. You’re absolutely right, Ron Athey was the first feature-length film documentary that I made. That was another scenario where we were friends. I was friends with most of the people in the film before I made the film. This art, and this living—for me, it’s [about the] experience. It’s “Let’s make food, let’s make a movie, let’s make love, let’s make happiness, let’s make something together.” A lot of these relationships have already been established in that vein and then we move on, and making a movie just becomes an obvious outlet. Each case was something like that.

Aggie, your new doc about your mother, Agnes Gund, is an especially personal project. Why was now the time to make a movie about her?

As a documentary filmmaker, many people in her world have said to me, “Your mom’s great! When are you going to make a movie about her?” I’ve always said, “Never, never, never.” [Laughs] I was very clear about that. But then she did this incredible [philanthropic] things. She didn’t talk about it, she didn’t say she should do it, she just did it! In the French Revolution, they called it “the propaganda of the deed.” I just needed to add to that, to amplify that as something for all of us to aspire to. Nobody can do exactly what she did. Nobody can do what you do. Everyone can do something, and we don’t have to be constrained by the mainstream media or advertising or tradition. We can actually use our imagination to do something different, that responds to our gut instincts, that responds to our intuition. We can follow our intuition to places where the mainstream media, advertising, the education system, and other things won’t lead us. Art, to me, is what can lead us there. I want to share. I want everyone to feel the same way I do about art. I feel like art is our salvation as individuals, as a community, and as a society. It needs to find a path forward, both to heal past wrongs and current wrongs, as we’re experiencing right now in our government—the legacy of slavery, the history of anti-Black racism, and the violence that this society was founded on. It is such a violent society. We need to be able to heal, and then to move to something that’s more just and beautiful.

Fairly early in the movie, you ask your mother if she wants to see a rough cut of the documentary. Has she seen it yet? If so, what does she think of it?

[Laughs] As in, does she still not want anyone to see it?

It was very funny when she said that to you in the car.

It’s absolutely what she said! I think she understands this part. I think there are moments when I can speak about the bigger picture, or other people speak about it. She obviously is an exceedingly humble and shy person who shuns the spotlight. That’s just a fact. It made making a film about her extremely difficult, because here I was saying, “You’re a good person, you should have a film made about you,” but the reason you’re good is that you don’t want the film made about you. So that was a challenge. I feel like I tried to foreground in the film and make it clear that she doesn’t want the film made. But she deeply believes in the end of mass incarceration, that this [moment in history] requires a reckoning, and that she can speak to that. To anyone who is listening, even if it’s a small group, even if it’s just me, even if it’s a few friends. We all know it’s bigger than that. She does have a voice, and she can use that voice to create a world that would benefit everyone.

The movie is full of examples of your mother’s delightful sense of humor. The interview scene with filmmaker John Waters, for example.

[Laughs] That was the best, the very best!

Do you share her wit, or would you consider yourself to be more serious?

I think we have very different senses of humor. I definitely think hers is much drier and wittier. I laugh freely and I crack jokes constantly. You wouldn’t believe how many of those little clips in the back seat of the car there are. In a way, her priorities are right, but that means that they’re not always the same priorities as yours. Here I am, trying to get her to speak and be interviewed, to tell me about X, Y, and Z. She spent so much time in the conversations with people, asking them questions.

Were you aware when you were growing up of what, exactly, your mother had hanging on her walls?

I was and I wasn’t. When she moved to New York City, I was out of the house. I will say that is when it became clearer, certainly to me. Maybe because I was older. I think with her being in New York, she was freer to do it. There are certain pieces that I know were in the house when I was little. They’re just burned into my psyche. The Mark Rothko piece has been in our house my whole life. I knew it was there, and I loved it. I felt a connection to it. Also the Hans Hofmann, which is in the Museum of Modern Art show. It’s a very colorful block-color piece. That was always there while I was growing up. There was art around, for sure. We moved several times, but I can remember where the Rothko piece was in every single house. This was when things didn’t change as much as they do now in her house, where art is being loaned out constantly and new art is being hung. It’s just a beautiful, living gallery. Growing up, there were fewer pieces and the thing that changed would be the Christmas tree. A Christmas tree would come, and some furniture had to be moved. We would decorate the Christmas tree, and I would always think of that in relation to the art that was still on the walls.

Aggie’s [interest in] philanthropy and activism is equal to her talent for art collecting. Did you inherit your mother’s activist spirit?

I certainly am an activist, and have been from a young age. It’s hard to know when and why those things happen. I’m sort of a 50/50 person. You’re 50 percent nurture, 50 percent nature. I think that’s just the default when we don’t know the answer. I was raised with three siblings, and they’re not like me. Did I inherit a gene that they didn’t necessarily inherit? I think a lot of it came from being queer, [where] you are always having to understand the language of the mainstream as well as that of your own perspective and your own view of things. [You have] experiences which you know to be different from the mainstream story you’re being told. I think that allowed me, right away, to know that there was something else. I think art is a portal as well. Whether it was nature or nurture, I did inherit from my mother [the ability] to see the world through art. That is a way toward understanding, a portal [through which we can see] a different path forward, and then to understand injustice. She was always a feminist, although she wouldn’t use that term. [Laughs] I still don’t think she would, even though I’ve argued with her (probably once every 10 years), “Go ahead, say you’re a feminist.” “But why?” Even this action of Art For Justice, she wasn’t going to talk about it, she just wanted it to change. She wanted to get funding and support to the people who are doing the work, who knew what was wrong and are systematically solving it. Art For Justice is so different as a funding mechanism because it prioritizes art and activism together. That’s my sweet spot. That’s where I live, where art and activism are the same thing.

Because this is such a personal film, what are you hoping the audience takes away from it?

It is a really personal film, and for that reason I feel like I partly had to make myself vulnerable. But I also feel like there’s not really an argument with inspiring people to think about their community and their relationships within their family and in their country and in the world. I think that’s what I want people to take away. Like these conversations show, you talk to people who you don’t know everything about, or who you don’t agree with on everything. Also, the way she sees the world through art. People have said to me, “I thought artists were just old dead white guys. That was the definition I was given.” It’s horrifying to realize that that’s still what people are taught. If you go to museums, you’re still going to see Picasso and Matisse and Renoir and Rembrandt. All these old dead white guys. These are the names that will come up if you say “artist.” People aren’t thinking of Faith Ringgold, Hank Willis Thomas, Glenn Ligon, or Teresita Fernández. So many older, younger, and established artists. Some are performance artists and some are sculptors and some are painters. Julie Mehretu’s artwork is very abstract, although she will say each piece is about an experience that is very concrete to her. Mark Bradford’s work hangs on gallery walls. It’s incredibly powerful because there’s an energy that goes into it, and that spirit reflects right back out at you. It’s not about what the pieces are. I’m looking around the room I’m sitting in now, and I see all these different pieces that mean so much to me. One is made by my daughter, one is made by a friend, one is an image that everybody really loves and connects to in our family. The piece doesn’t matter. It’s the idea of having that energy in the room and having that as a part of our language. Our ability to communicate is based on a language of seeing. What do we see? That then dictates what we know. It’s a cycle. I would love people to think of art that way.

For more information on Aggie, visit aubinpictures.com/aggie.