Torn between Two Countries

Artist Moe Penders dives into a turbulent family history.

When Moe Penders first came to Texas in 2009, the nonbinary photographer envisioned quickly completing veterinary paramedic and zookeeper courses at Houston Community College, and then promptly returning to their native El Salvador.

Twelve years later, Penders, 32, has built a life in the Bayou City by embracing their passion for photography, building up a vibrant studio practice, and coming out publicly as nonbinary. Throughout those years, they have won acclaim for their art and worked to uplift Latinx trans and gender-nonconforming artists in the city.

The Beauty of El Salvador

El Salvador has served as both an emotional and creative anchor for Penders. “All of my work is about home, and different aspects of home,” they explain. “I think it’s also informed by the fact that I’m not there, but I have the desire to be there. As a country, it’s beautiful. I love the people. I love being there. There’s this constant desire of wanting to go home, but at the same time not feeling that I can live safely or freely there in my identity.”

In 2018, Penders presented Cultura, a photography exhibition at the Alabama Song art space that featured their photographs of a series of objects representative of El Salvador, ranging from candies to stamps to flip flops. Reviewing the show in Glasstire, critic Reyes Ramirez observed, “Penders subverts [the stereotypes] of Salvadorans as only being miserable, but instead [presents them] as a people of vibrancy, sustenance, and leisure. What happens are thoughts and questions and revelations that go beyond the images: Can a culture be both old and new? Both ancient and evolutionary? These photos are.”

Having grown up in a conservative family, it was not until Penders arrived in Houston at age 20 that they had the freedom to explore their identity. “Over time, I understood more about my gender and identifying as nonbinary,” they recall. “Being here in Houston has given me the space to grow more into myself—to have the language for it.”

Creating Opportunity

Penders’ artistic journey in Houston has not been without struggles. The need to generate enough income to pay the rent resulted in a constant battle to carve out the time to create photography. For two years, they lived in a tiny artist studio east of downtown.

Penders has striven to provide a platform for promoting other queer Latinx artists, most notably in 2019 by curating the Sabine Street Studios exhibition El Chow: Mango Verde. “As queer people, we tend to be overlooked and cis hetero people are given opportunities before we are allowed to,” they told Glasstire at the time. “It is a constant conversation I have with my trans and non-binary peers. El Chow was created with the intention of creating space for my peers—for the people who don’t get the opportunities, and who don’t usually have support. We make it happen however we can.”

Connecting with Family

Penders was born in El Salvador in 1988, the child of an American mechanic and a Salvadoran mother, toward the end of the country’s long and brutal civil war. A stark emotional void was created when Penders’ father died suddenly and unexpectedly in a car accident in 1992, when Penders was only 4 years old.

“I was so young that I barely have any memories of my father. I only have short, little flashbacks of him,” they explain. “When I was 10 or 11, someone had a video of him, and I heard his voice. Now that I’m older, I want to be able to hear his voice. It has a lot to do with remembering, and being able to remember.”

One tangible connection to Penders’ father was a cache of photos that their grandmother and mother had collected and stored in a suitcase. Yearning for contact with him, the young Penders would pull out the photos of their father and examine them frequently over the years. They credit that experience with helping to nurture a deep love of photography.

Penders’ artistic studies continued at the University of Houston, where they focused on film-based photography while earning a bachelor’s degree in photography and digital media.

Memory and Metaphor

In 2019, Penders decided to delve deeply into the memories of their father when they created a dramatic and moving series of works entitled Volver, or “Going Back.”

Penders was eventually told by several acquaintances that their father had actually been murdered, but their mother and grandmother refused to discuss the matter.

“When I started the body of work, I wanted to know exactly what had happened,” they remember. “In reality, I don’t think anyone knows but him and, if anyone else was involved, that person. Creating the work entailed a lot of processing of his death, which as a child I wasn’t allowed or able to do.”

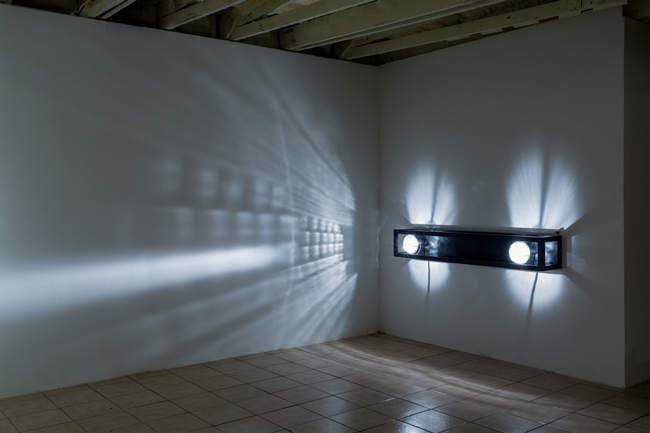

Penders found the headlights of a Volvo P1800 sports car, the model driven (and frequently worked on) by their father. The artist created a sculpture out of the headlights, which could be turned on and off to haunting, dramatic effect.

“The presence of the car and the light is very important, regarding memory as well as metaphors in the work,” Penders explains. “[The work] also marks a time in Salvadoran history [when] the U.S. funded the war. This is important, as the only period when my father and I were alive at the same time was the last four years of the war.

“Like many Salvadorans born during the war who lost parents, I never found concrete answers. My father’s death marks a moment in the history of El Salvador’s political turmoil. My research focuses on materials and memory [of] a moment in the nation’s history that continues to impact countless individual lives in El Salvador.”

Veteran gay Houston artist Michael Golden, who taught Penders watercolor painting at Houston Community College, has collected several pieces of Penders’ work, and has watched as the artist evolved over the years.

“Moe’s work is strong because it is so personal,” he observes. “It’s a visual struggle to come to terms with duality—of country, of gender, of seeing things as black or white.

“Moe uses both memory and ‘forgetting’ to create works that are open-ended and poetic. I feel that the simpler the image, the more Moe has come to terms with the subject matter. The more ethereal, narrative works are the ones that still bring up deeper emotions in Moe, at both ends of the spectrum.”

For more information on Moe Penders, visit moependers.com.

This article appears in the August 2021 edition of OutSmart magazine.