The Pink Triangle’s Legacy

Dr. Jake Newsome to speak about the original Pride symbol on June 7.

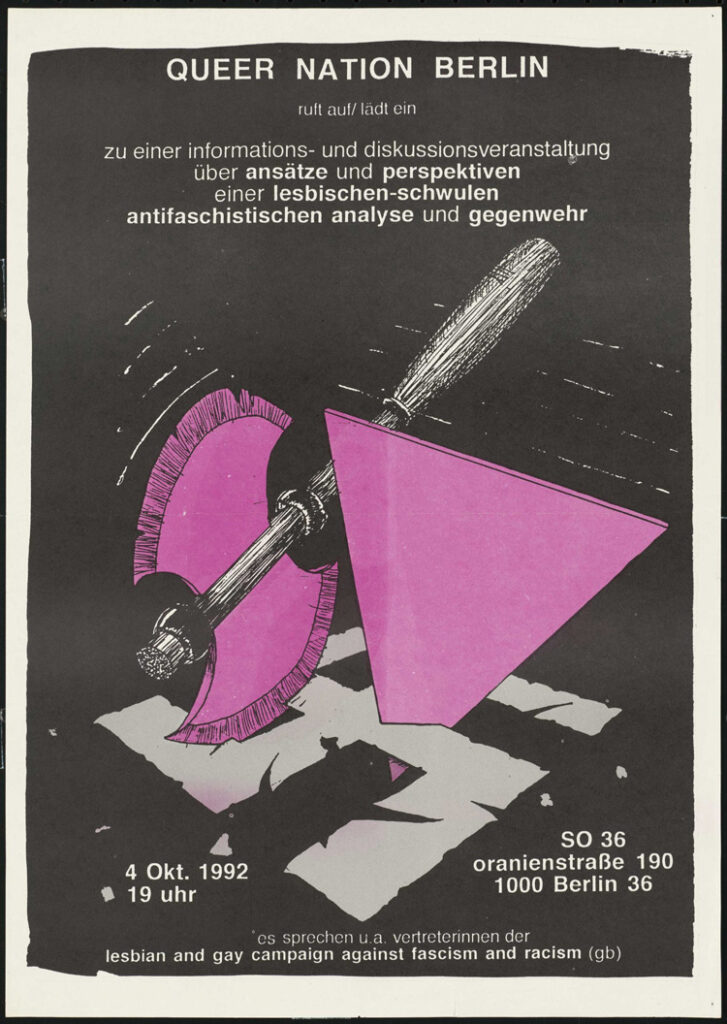

Today, the rainbow Pride flag waves proudly outside of bars, businesses, and homes, signaling to the general public that members of the LGBTQ community are welcome and affirmed in those spaces. Before the colorful flag first appeared in San Francisco in 1978, the use of the pink triangle—a symbol used in Nazi Germany to identify members of the queer community—was reclaimed by queer activists worldwide.

Dr. Jake Newsome, a scholar of American and German LGBTQ history, has compiled his extensive research on the symbol, its impact on queer liberation, and its historical significance in his book Pink Triangle Legacies: Coming Out in the Shadow of the Holocaust. On June 7, Newsome will speak at Holocaust Museum Houston and share more about the history of the pink triangle and the lessons its meaning inspires for the queer movement today.

“I was first introduced to the history of the Holocaust in college. I am not Jewish, so I didn’t learn about the Holocaust through family history, and unfortunately I didn’t learn about it in high school,” says Newsome, who grew up in rural Georgia. “It wasn’t until I was in college at Valdosta State University that I even knew that there was this thing called the Holocaust. This was around the same time that I was personally beginning to come out and grappling with my identity as being gay, wondering how I fit in with the world and with history.”

Newsome began his research by diving into the literature. “I ended up trying to learn a lot about queer history through books. It suddenly dawned on me that none of my teachers ever talked about what happened to people like me during the Holocaust, or what life was like for LGBTQ folks living in Nazi Germany,” the author explains.

Living in Buffalo and attending graduate school at SUNY’s Buffalo State University, Newsome ventured out to find community and was surprised by what he found. “I learned that queer prisoners in the camps were forced to wear a pink triangle badge. At the same time, I went to my first gay bar in Buffalo and saw pink triangles used as decorations in the bar,” he recalls. “I had this moment when I wondered if this was the same triangle that I was learning about in Holocaust history. That really set me on this path of trying to learn not only the history, but how this symbol went from the Holocaust to a symbol of the gay community in America 70 years later.

“Before the Nazis came to power, Berlin was the gay capital of the world. Queer people enjoyed a level of freedom and tolerance that no one else had in the rest of the world. Germany was a democracy, and there was this vibrant LGBTQ community and LGBTQ activism. The world’s first gay-rights activist organization was formed in Berlin before the Nazis came to power,” Newsome says. “And all of this was able to be radically destroyed and driven back underground within a matter of weeks.”

Newsome explains that the Nazis, having inherited Germany’s anti-gay bill, amended that law in 1935 deeming the original too constricting on their ability to arrest queer people. Named Paragraph 175, the new bill made all “indecency” between men a punishable offense. “They intentionally left [the new law’s] language very vague so that they could interpret it however they wanted to on a case-by-case basis, with the goal of arresting as many men as possible and sending them to concentration camps.

“Although Paragraph 175 applied only to queer men, other members of the LGBTQ community were also persecuted by the Nazis,” he says. “That fact often gets glossed over in history. The Nazis treated trans women as cross-dressing gay men, and they were also arrested under Paragraph 175. The Nazis used a range of policies and laws to arrest lesbians and other queer people. They were also sent to concentration camps by the thousands and were marked with a black triangle—the badge for so-called ‘asocials’ (or social deviants).

“The Nazis wanted everything that they did to have a legal backing to it—which I think is important, because the right wing today is passing all of these laws because they want everything to point back to a particular law or policy.”

Newsome describes the law further, saying, “After that 1935 amendment, essentially any type of evidence was enough for an arrest to persecute queer people. This was anything from two men holding hands to being seen kissing, or spending the night together. A lot of times the Nazis would arrest one man who they knew was queer, and essentially torture him to give up the names of other people in his circle.”

In the 1970s, almost three decades after World War II came to an end, Europeans who were witnessing the impact of New York City’s Stonewall Riots decided it was time for them to stage their own movement. Newsome explains, “There was a group of European gender-nonconforming radical queer activists who went to their fellow cis gay activists and said, ‘Look, just by being gender-nonconforming, we are immediately identifiable by society. [But you cis gay men] could pass as straight. You need to understand [that] if you were easily identifiable as gay, you would also face persecution.’”

The groups came together to determine what a gay symbol would entail. “Germans didn’t have to go very far back in their own history, because there was already this pink triangle symbol that was forced upon gay people. They decided to reclaim that symbol, and try to rob it of its negative power,” Newsome explains. “By wearing it by their own choice, they were effectively going to tell society that being gay is in no way shameful or criminal—that it should be, in fact, something that they identify with pride and resilience.

“There were several American activists in Berlin at the time that brought that information about [Nazi] history and the pink triangle back to New York in 1974, and it took off all across the United States, Canada, and jumped the Atlantic back into Europe as a gay-rights symbol,” Newsome says. “The symbol acted as two things simultaneously: a historical warning of what happens if homophobia is left unchecked, and as a rallying cry. If you saw someone walking down the street with this pink triangle on, you knew that they were part of the community. It was a way to identify each other to help build a community and solidarity, and help turn a queer identity into something that you could have pride in.”

Newsome’s fluency with the history of the pink triangle’s origin in Nazi concentration camps, and how it resonates today as a badge of honor, will be the focus of his Houston lecture. “I think that folks will come away with a better understanding of not only what happened to queer people during the Holocaust and in the years following, but also with a better understanding of why that history is so incredibly relevant for today,” Newsome says. “I think that this story has something to tell us, more broadly, about how societies decide what’s important to teach as history—and the repercussions of silencing and erasing chapters of history.”

WHAT: Free LGBTQ history lecture by Dr. Jake Newsom

WHEN: June 7, 6:30 p.m.

WHERE: Holocaust Museum Houston

INFO: hmh.org